I got out over my skis a little.

Part of my plan for the year, just at home, is to read more. I’m aiming for a couple of books a month and so far I’m a little above that. I had been reading Slavoj Zizek’s Living In The End Times. I’ll take any help I can get in terms of putting together the impact the internet has on lived experience, even if it comes in the form of a rambling philosophical monologue.

And that’s why I pointed at a student whom I knew had a masters in Philosophy and said, “Yeah, it’s like a Lacanian objet petit A.” It’s never a good thing when the lecture is going well enough that it allows you to discover an underlying structure that has caused you to position things a certain way.

I structured the lecture as “Postmodern Outliers.”

If you’re thinking seriously about teaching people beer, you need to come up with some way to teach things that exist right up to the minute on an ahistorical basis. If you’re reading this, chances are you started thinking about beer some time around the 2007 boom. You’ll know that there is a delineation point sometime around 2017 when stylistic tradition is more or less out the window.

In this class, I’m teaching beers like Blood Brothers Guilty Remnant, a White Stout with coffee, lactose, and vanilla. I have Collective Arts Guava Gose, a fruited take on a style that was really only introduced to North America in 2013 or so. I have Rorschach’s Hedonism Passionfruit Orange Guava Sour Sorbet IPA, which contains more ingredients than you really want to think about.

According to Lacan, objet petit A is an externalized cause of desire, an otherized object that because of its profound sublimity becomes a point of fixation. That is to say, a lost object which causes a longing or a desire and which can really only exist through experience and, to touch on a point from several posts ago, qualia. It needn’t necessarily be nostalgia based, but since we are creatures made up of experience, it frequently is. The past is unattainable and therefore boundless in its ability to prevent you from reaching it.

I can picture, for example, although I cannot google a picture of it since it predates the internet, the candy bins. When I was very young we would shop at the Loblaws at Bayview and Moore, and I can picture, 30 feet in advance of the bottle return at the southeast corner of the shop floor, the bins which held Trebor candies. If you had been very good you would sometimes be treated to a single candy on the way through the store. In practice, I don’t know if there was a small coin deposit or whether we were sampling the wares surreptitious. I can envision, in my mind’s eye, the blue- purple wrapper with dull orange gold print on a Butter Rum Chew.

These are the things of which your palate is made up. Not just yours, but everyone your age. Different items, maybe, but they existed contemporaneously. Items that were so desired and which existed with such cachet that they saw you off on your bike to Becker’s or Mac’s Milk or the Hasty Market.

When you realize that is the case and that it must be uniformly the case across history as we have not changed very much, human beings, it does make you question the legitimacy of canon.

Imagine growing up in a small town northeast of Leeds in Yorkshire. If you’re born during or just after World War 2, for the first ten years of your life, everything is rationed. By 1940, bacon, butter, and sugar were rationed. Tea, jam, biscuits, breakfast cereal, and dried fruit were all rationed subsequently along with meat and dairy products. In 1949, when they ended rationing for sweets, the rush on shops was so great that they had to reintroduce rationing until 1953.

In 1951, Greene King introduced Abbot Ale. In 1958, Fuller’s introduced London Pride. They taste of tea time; of all the things that you were not allowed to have. Black tea and brown sugar and biscuits and jam and marmalade and honey and breakfast cereal and dried fruit. If you were from Wetherby, it would probably be Tetley’s that possessed those qualities you would have longed for as a child.

Michael Jackson, who set us on this path, was from Wetherby.

I wrote a couple of weeks ago that I was saddened by the changes in the UK brewing market and that I hoped there would be adequate honey still for tea, but that is a reference to a poet called Rupert Brooke. I don’t like tea, at least in the English sense. I grew up with United Church ladies who drank Orange Pekoe, and they might have migrated here from England after the war. I will sometimes drink Genmaicha.

The thing is you simply can’t ascribe cultural primacy to an individual palate in a genre as culturally and informationally dependent as beer. You can’t have nostalgia for someone else’s objet petit A. You could develop a taste for treacle and marmalade, but if you’re under forty and living in Canada, it’s quite unlikely that you grew up with it and when you’re an adult it’s hard to fixate on the new.

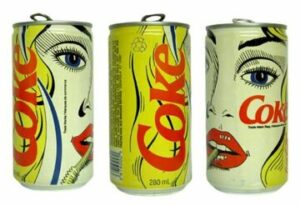

We grew up in a time of unprecedented plenty. You wouldn’t believe the amount of confection introduced between 1980 and 2000. I’m old enough to remember New Coke’s Roy Lichtenstein pop art cans displayed unopened as art on a childhood friend’s bookshelves. It was a time when they weren’t designing food for complexity, but for impact.

I’ve found that one of the greatest sources of commonality for qualia in sensory instruction is halloween candy, because everyone, regardless of socio-economic background, ended up with more or less the same treats. Rockets and warheads, tart and sour. Skittles and jolly ranchers, vibrant and fruity. Punchy, citric acid laden monstrosities of flavour that you’d divert across neighbourhoods to a better convenience store for despite the potential of a lecture from your parents.

And I’ve just about lowered my pointing finger when someone says, “but is any of this beer?”

Of course it is. In the same way that the flavour profile of an ESB is desired by a certain subset of English expatriates and weirdos like myself that have developed a taste for it through inculcation, these are the flavour profiles desired by people who grew up with their own set of experiences.

What is a New England IPA but beer for people whose fridges were filled with purple stuff and Sunny D? What is fruited Kettle Sour but beer for people who grew up sucking on enamel destroyingly tart candy that would burn in on your tongue? What is a White Stout but a Tim Horton’s Iced Cappucino that hasn’t been put through the slushie machine?

You can’t replicate the ache of nostalgia for the barest hint of sweetness in people who grew up without privation. The session in the pub with eight pints of bitter is for those who suffered in childhood with the privation of that sweetness. You can only replicate that sharp single flavour, that firework of dopamine, that desire to be out of your house on your bicycle with the wind in your spokes in search of the forbidden. It’s an identical function, a gap filled. We’re in the desire business, after all.

The worry shouldn’t be that people desire something you don’t like. The worry comes when you wonder what we have come up with in the space outside of beer since 2000. What new confection is there? Or have we sunk into a period of privation and anhedonia? That is to say, if you were 25, what would you have wanted in 2009? How do you get people who grew up with the internet to desire physical objects? Did they ever go outside? That’s the issue we face, and that’s what you have to worry about.

Interesting, certainly.

It is true a Turkish delight-type effect characterised Fuller ESB – and many other bitter ales postwar (eg. Ruddles, Courage) – yet I have no reason to think the taste did not exist earlier, and was revived/boosted after war’s depredations on beer quality. Top yeast, open fermentation and lack of methodical cooling had a lot to do with such flavours, all traditional and long predating the sugar revolution and sweets industry.

Maybe you could argue it was the other way around, sweets provided in innocent form, as it were, a taste the country’s traditional ales had reserved, necessarily, for those who reached drinking age.

Many modern IPAs taste of tropical fruit or grapefruit, and Americans always loved fruit juices, yes (long before onset of Sunny D and Purple stuff) yet beer tasting of earthy blackcurrant or German metallic type hops satisfied amply until the 1970s…

The development of the grapefruity Cascade hop in the 1960s was of course not foreordained, much less that early craft brewers would bank on it, much less that it would take off in the market.

It is always hard to know “who came first” in these things, it seems finally an endless series of mutually reinforcing events. Eg pumpkin beer must have kickstarted pumpkin muffins, doughnuts, teas, etc.

Very astute insights, Jordan.

If you are willing to concede that context is 90% of anyone’s personal truth, then it’s even more incumbent on the person contextualising their experience of something, to make a resonant impression for someone else by carefully choosing the most accessible reference point for that person, in order to have a shared experience.

This is a huge proponent of the notion that there are no wrong ways to talk about beer flavours only more specific or, even, more varied ways to talk about it. Frame of reference is everything. If one makes reference to a specific type of Swedish salt licorice, Lakrits, for example, they better be able to at least describe the subtleties of anise, fennel and the sharpness of a sturgeon caviar or sea water or any number of other flavours that might illustrate what might otherwise be an obscure reference to anyone else.