In the run up to week five, the first of this year’s completely redeveloped lectures for the Beer Appreciation class at George Brown, I had some problems to contend with. As stated earlier, the sheer volume of imported American Craft Beer that had fallen out of the LCBO chain made it so that redevelopment was inevitable.

It’s only when you start to break down what I do that the inherent weirdness of it dances into the spotlight. I am beholden to an accredited College on a formalized academic basis, but I have no subject matter oversight to speak of. I have to stand in front of a group of people for four to eight hours a week (depending on course load) and facilitate learning outcomes pertaining to sensory input that involves alcohol. I’m not beholden to say, the Cicerone Program or the BJCP in any particular sense. I don’t have any training to speak of, but I’ll have been doing it for seven years in May.

Whatever canonical body of knowledge on the subject I’m teaching might exist shifts like sand under my feet. Canon is possible in literary endeavour or scientific pursuit or even philosophy. The text is, barring periodic censorship or redaction, the text. This is to say that Hamlet remains Hamlet. Interpretations of it, approaches to it, stagings of it will change over time based on temporality, but the text hasn’t really changed in the last 419 years. Some wag is going to point out separate folios, but will, deep down, understand the point.

In my discipline, people are still arguing over what Craft Beer might actually be.

Consider this from an academic standpoint: In the first four weeks of classes, I’ve had to update the slides in the lectures to the 2021 BJCP Standard for purposes of uniformity. Consistency in the conceptual elements of Craft Beer is impossible, but to the extent that you can jolly it along so that people have contemporary information, you ought to. The difference between the 2008, 2015, and 2021 definitions of American Pale Ale are, from an ontological standpoint, teeth grindingly enervating.

Take Sierra Nevada Pale Ale for example. It’s the quintessential American Pale Ale. I have been teaching it since it came to Canada in cans. I’ve been to Asheville and I’ve tasted that beer with Steve Grossman. It has changed, subtly, over the course of the last five or six years. Instead of white grapefruit and pine from the Cascade, it has taken on a little mango and it is probably less assertively bitter, although it is still bitter.

For maybe a half decade, I’ve watched this happen very gradually as groups of students have broken down aromas and flavours. One taster might be off, but we’re talking about sequential groups of tasters in aggregate. I’m talking about hundreds of self selecting, motivated people in groups sequentially over time. I asked Stan Hieronymous about Cascade and whether he thinks it has taken on a mango note because of climate change, and he suggests that people might be selecting for it. I doubt that Sierra Nevada, who has the first choice of Cascade because of their size and the fact that they use whole cone hops, would choose to make that change. Maybe. But the fact remains that it has shifted somewhat.

So, canonically, Sierra Nevada Pale Ale is the quintessential American Pale Ale, except that it has demonstrably changed in character since 2018, let alone from its advent in 1980. The definition of what an American Pale Ale is has also changed dramatically. Additionally, from a practical standpoint, you don’t really know what condition the beer was going to be in when it showed up in the classroom. Fresh shipment? Six months old? To place it within a narrative framework describing the arc of development and influence within a genre of extant products that also shift dramatically on an ongoing basis in terms of their properties, reputation, and reception is to deal constantly in teleological prevarication.

You know. Bullshit.

And that thought process? That pertains to approximately 15 minutes of actual in-classroom material. This level of epistemological uncertainty is why I build in jokes. You can’t teach people about beer with a straight face. It’s absolutely absurd. What I’m doing is more or less stand up pedagogy.

——————-

Why would you teach people about American Craft Beer in Ontario anyway?

I was explaining to Evan Rail, my commissioning editor for Good Beer Hunting, that Ontario’s border is extremely non-porous. When you think about how little American Craft Beer is here, and how we are still embroiled in disputes about whether you can bring in beer for personal consumption from Quebec, you begin to get the picture.

In America, you had large regional breweries distributing across multiple states, which made the expansion of craft beer as a cultural package a lot simpler. In Ontario, traditionally, we’ve had maybe five extra-provincial breweries on shelves consistently. McAuslan, Unibroue, Big Rock, Moosehead. I don’t know if protectionism was intended, necessarily, but it certainly worked out that way.

Creating a lecture on Ontario’s beer from 1984 to 2011 forces you to throw out some assumptions. For one thing, the idea that breweries are going to exist indefinitely is a non-starter. Brewing is a generational business and always has been. We’re used to the idea of Molson and Labatt, but realistically, continued existence is aberrant. Selling your brewery instead of closing it means you succeeded.

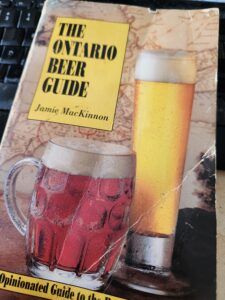

I have in hand a dogeared copy of Jamie MacKinnon’s 1992 book The Ontario Beer Guide. Of the named breweries in the table of contents, two continue to exist on an independent basis. I’ll break it down:

Brick is now Waterloo and is owned by Carlsberg. Conners died at least twice. Creemore Springs was purchased by Molson in 2006. Hart might have quietly been rolled into Scotch Irish and then Kichesippi at some point about a decade ago. Lakeport was bought by Labatt and decommissioned with extreme prejudice before the facility was purchased by Collective Arts. Niagara Falls Brewing was bought by Moosehead and the equipment was shipped to Hop City in Brampton. Northern Algonquin was run out of Formosa (whose current website is worth a chuckle) but purchased by Brick in 1997 and shuttered. Northern Breweries were essentially victims of their own geography and shuttered in 2006. The Pacific Brewing Company probably continues to exist in BC, but not St. Catharines. Sleeman purchased Upper Canada and was in turn swallowed up by Sapporo in 2007.

Great Lakes and Wellington are the only ones that made it. If you expand it to brewpubs, the long term success rate is 7/31 if you’re applying “success” generously.

Granite is the most successful continuing entity. Amsterdam is owned by Royal Unibrew. Denison’s is on its third set of ownership. The Kingston Brewing Company is still independent and is the best beer bar between Toronto and Ottawa. Tracks, Ceeps, Huether Hotel, and the Pepperwood Bistro probably all still exist at some nebulous level. They might collectively account for a thousand hectolitres a year.

Long term independence at a level beyond stability has been achieved by exactly three entities that existed in 1992.

Look at this poster from the OCB in 2005. 25 Breweries making 102 beers. 19 years later, 12 of them continue to exist as independent entities, 8 have been purchased, and 5 have outright closed. As I understand it, most of the larger independent entities are for sale. I’ve seen EBITDA projections and asking rate for one of them.

Objectively speaking, you can’t teach people about the history of beer in the province of Ontario without discarding the concept of independence entirely. If you’re going to be intellectually honest about it, you have to count selling out as success and closure as failure not only from a business standpoint, but from the standpoint of conceptual continuity. I can only teach people about things that continue to exist and that continue to be more or less themselves.

Plus, a series of cautionary examples makes for an extremely amusing narrative framework. I can tell people which brewers worked where and how ideas cross pollinated. If craft beer is anything, it’s the propagation of a cultural package, and I don’t care about ownership anymore. It is not of deontological consequence. We’re past that now. I just want to tell you how we got from 1984 to 2011.

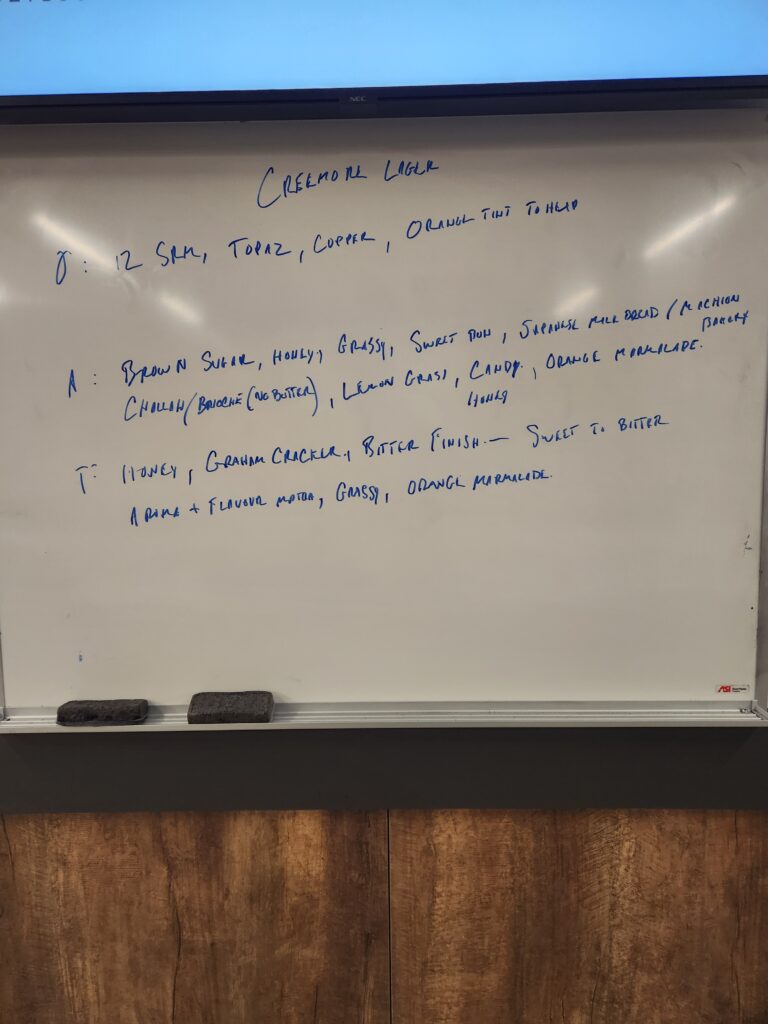

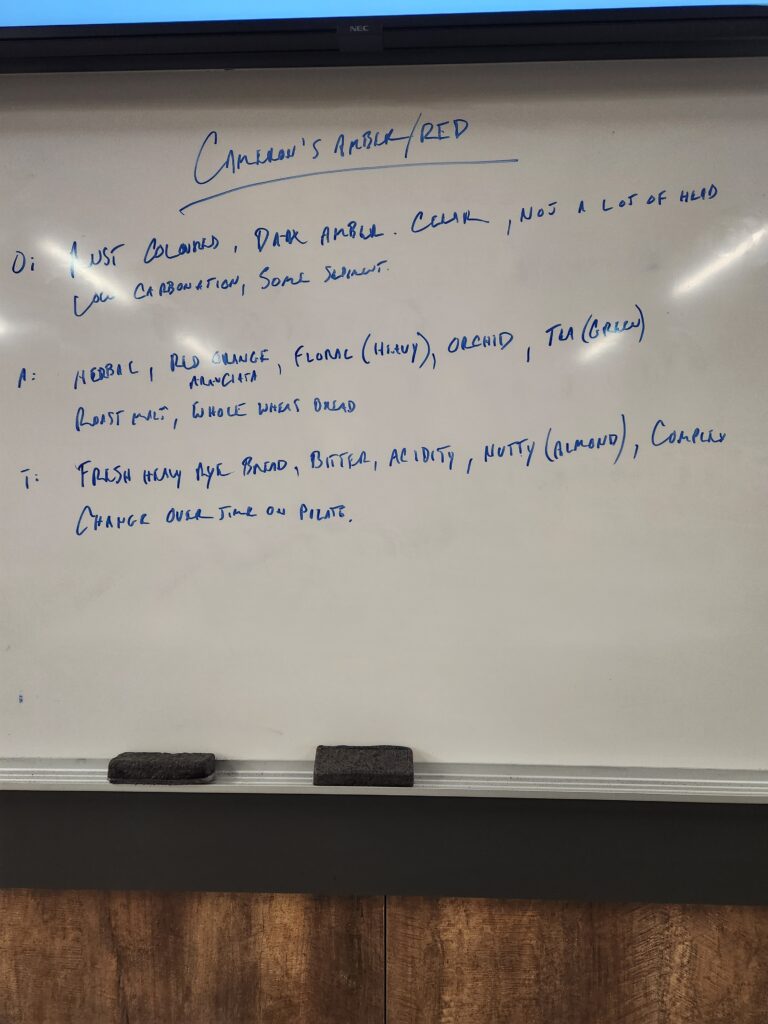

That’s why the current slate of beers includes Waterloo Dark, Wellington SPA, Creemore Springs Lager, Muskoka Cream Ale, Steam Whistle Pilsner, Beau’s Lug Tread, Cameron’s Ambear Red Ale, Great Lakes Canuck, and Amsterdam Boneshaker. It would include Mill Street Tankhouse if it were LCBO available. The Ontario Pale Ale might be maligned, but it existed.

In the long term, you either sell out or fail. The part that matters is what you do in the meantime.