When I got hired to teach in 2017, I was a subject matter expert. I didn’t have any teaching experience to speak of, except for having been an instructor at a music camp in high school. I also had a dread of public speaking which I overcame in about a month because all of my income was suddenly derived from standing in front of people and talking.

When I took over, Jesse Vallins, now the head chef at Toronto’s storied Barberian’s Steakhouse, had been at it for a semester and was still using slides from the previous instructor: Troy Burtch, from Great Lakes. Troy’s a good friend, and all time Ontario Craft Beer guy, but he had a background with Labatt, and for that reason he had placed a lot of emphasis on macro products. He thought about it differently than I do, and you can’t teach someone else’s material. He also had a lot less choice in the market to work with when he started.

Regardless of what I wanted to do with the material and structuring it in the week of prep time I had, they had already purchased the beer. The first time around, at least, I was stuck with a set of products. All I could do was select the order in which they’d make an appearance.

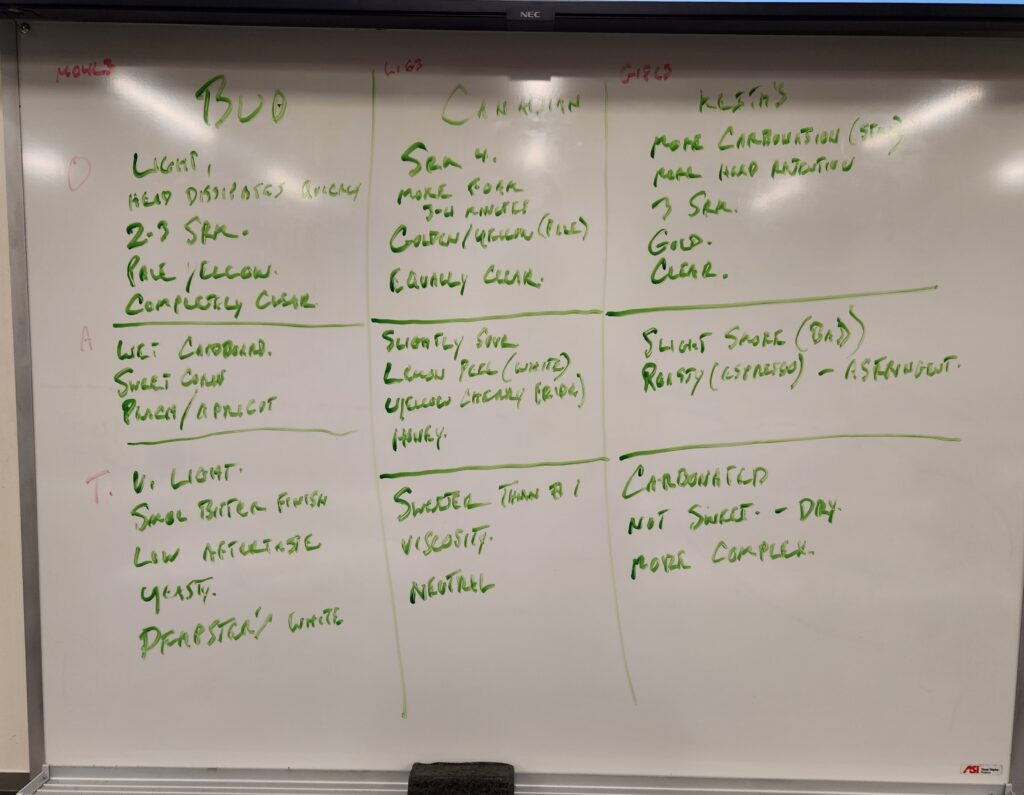

This mostly made sense, except that I had Budweiser, Molson Canadian, Alexander Keith’s IPA, and Moosehead left over. There’s nothing actually wrong with people enjoying those products, and I maintain to this day that even the snobbiest beer professionals should be able to enjoy them in the right context. That being said, there’s more interesting stuff out there.

“How can I get them out of the way?” I thought.

Well, maybe I can get the students to taste them side by side. If I put them all in a group exercise right up at the top of the course and get them to tell me what’s different about them, it not only ensures that all subsequent beers will be more interesting, it causes them to ask questions. A homebrewer I know once said it’s the equivalent of throwing them into the deep end without floaties.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s the best decision I’ve ever made.

I don’t believe in prescriptive tasting. I don’t think it works. “You should be getting this,” is impossible with beer. Each batch is subtly different, cans or bottles are of different ages and have been handled differently. Marketing copy is frequently incorrect, especially with craft breweries. I once went to a launch for Alexander Keith’s Cider where no less a light than Zoltan Szabo tried to explain to a group of beer writers what they should be getting. He nearly got laughed out of the venue.

I believe in the students. They walked in off the street half an hour ago, and they know what they’re about. It’s a self-selecting group of interested people. More importantly, I know a secret. My job isn’t really to teach them about beer. It’s to teach them to have a palate.

I learned this when I had a student that believed he simply didn’t have a palate. He couldn’t get the things that other people were getting. I think he was a smoker, and that’ll numb your senses. I could feel the frustration building in him as the course went along. And then, some time around when we got to Witbier he said, “it’s the same flavour as the griddled tortillas I had in Cancun.” He was so relieved, but what had happened is that he had relaxed and started to think about it as play.

Palate is the ability to express sensory data via language. It’s mnemonic, but it’s also mechanical. If he hadn’t been a smoker he would have been better about the mechanical part, but the mnemonic part is experience based.

That experience, when you sieve it down, is a series of what’s called qualia. The experience of eating a specific apple with all of its texture and acid and tannin. The blast of frigid wind on your shirtless chest when you open the window on a January morning. The sickly sweetness of a hothouse orchid at the Toronto Zoo. The immediate snap of pain when you roll your ankle and the indignity of walking it off in public while assuring people you’re fine. The high pitched beep of your Gran’s hearing aid when you greeted her with a hug. How she would shakily sing “how do you do my darling” when she saw you. The enormous corona and reddened dusk of a Lake Huron sunset. The aroma of denuded silver maples on the southbank of the Thames as you walk towards Blackfriars. A pint of Propeller ESB at the Economy Shoe Shop as Rick Mercer walks by.

You can experience qualia. You cannot pass them on. They are ineffable. They are private. They are yours. No matter how many of them you experience, they are not changed by other experiences. You can describe them if you think about it, but you can’t parse them enough to share them.

I have an entire classroom of them to work with. Lifetimes of memories, experiences, qualia. I’m a charlatan in the classical sense in that what I’m doing is a cold reading. Like a psychic with messages from the other side, I can ask a series of leading questions. “Is there anything fruity? Is there anything that reminds you of a bakery? What do you like about it? What do you hate about it? Oh, it’s floral? What kind of flower?” They all have different experiences of the same things. Halloween candy is a big one, believe it or not, having to do with the excitement surrounding it.

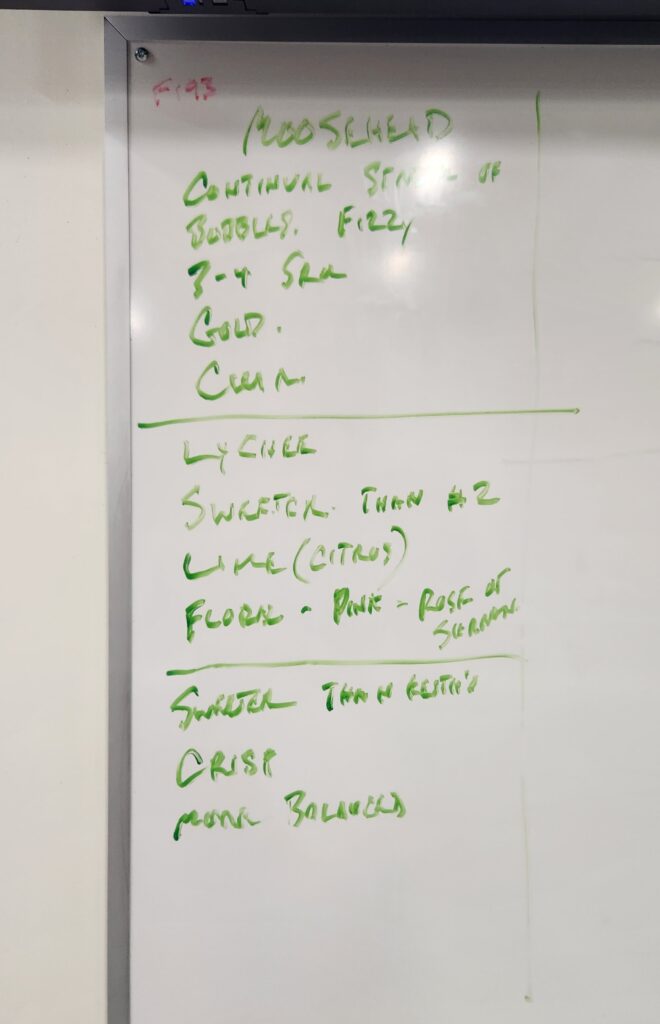

I need them to understand that there’s no wrong answer. If you perceive it, it’s there. I can tell you all day long that Alexander Keith’s has DMS in it, but it is way more effective to have a fellow in the back row say it tastes of preserved sweetcorn. I can tell you that Moosehead is effervescent and expressive of hops, but when one of the students says Lychee and another one pipes in with Rose of Sharon, suddenly we are not just in recall. There are murmurs of agreement. We’re collectively developing qualia, stringing language together in search of a palate. The input to output transition happens in less than an hour and it’s because we’re playing a game.

Along the way, I get to talk about off-flavours, levels of carbonation, the pH scale, and shelf lifespan, all from naturally occurring questions. It turns out they’re always very perceptive. They just didn’t know it.

So there we were, effing the ineffable. By the end of the class I’ve got sets of tasting notes we could use for marketing copy for McAuslan Oatmeal Stout and Muskoka Mad Tom from a group of people who didn’t know each other until two and a half hours ago. By the last fifteen minutes, they’ve collectively diagnosed the Side Launch Wheat we’re using for yeast sensory as being old and without any phenolic character.

My hope is that by the end of the six week course they’ll learn to slow down a little and appreciate things more, maybe develop more experience, maybe learn to direct that impulse. Some of them will be out there this morning paying more attention to breakfast or their morning coffee. Finding gradation and texture in their worlds.

I don’t really care whether they know exactly what a Cream Ale is at the end of six weeks. I’m playing for bigger stakes. And since I’ve done this exercise every six weeks for nearly seven years, I can tell you that Moosehead usually wins now that they’ve stopped intentionally skunking the cans.