(Ed. Note: I was bored and TPL has access to ProQuest. This is long. I’m not sorry for it.)

A friend of mine is good with computers. Periodically he’ll shovel me the sales figures for the LCBO on the three listed White Claw products. I’ve tried White Claw and it holds very little in the way of mystique for me; it’s ok. I would say that the Black Cherry one is probably the best of them. The fact is, of course, that my opinion of the quality of the product is more or less irrelevant given sales.

What does interest me is consumer behaviour. In order for a craft brewer’s product to retain shelf space in the LCBO, the beer needs to shift two cases a month. That’s 24 cases a year. Last week, one store in St. Catharines shifted 174 cases in a day of a single flavour. Extrapolating the rolling average sales, chain wide, that equates to 228,000 hectolitres a year. The only craft breweries in Ontario to get that large in our history are Brick and Sleeman.

It seems unprecedented, but it isn’t. It’s the same trick performed by the same magician. White Claw is owned by the Mark Anthony Group. The Mark Anthony Group is having a second run at something they did in the 1990’s. Mike’s Hard Lemonade is currently a legacy brand owned by Labatt in Canada, but when it came out in 1996, it exploded on the market like nothing else ever had. It was lightning in a bottle, not unlike the current proliferation of White Claw. If we look at them in conjunction, there may be parallels.

I hope that we’ll be able to learn something from the previous iteration of a trend this size. Naturally there are going to be situational details that do not line up, although the general arc of the trend is similar. Additionally, I’m going to write about this from a Canadian perspective, because those are the resources that I have access to. It’s worth noting that Anthony Von Mandl is based in British Columbia, so it makes some sense to look at a single market. Before we get to the advent of Mike’s Hard Lemonade in 1996, there are a couple of things you need to know.

1993

In Adelaide, Australia a pub and brewery landlord named Duncan MacGillivray invents what comes to be known as Two Dogs Lemonade. Contemporary sources have him as sparking the RTD Revolution, but as is typical with the history of alcoholic beverages, the Wikipedia entry makes it sound more homespun. As the story goes, he had a neighbour who had a lemon farm and was having trouble moving all of the lemons he grew on the local market. Mr. Macgillivray brewed a beverage with them.

That sounds like it’s leaving out some details, especially when you consider that Pernod Ricard bought the brand in 1995, the same year that it spawned the UK imitator Hooper’s Hooch. It doesn’t seem to me like a random strike-it-rich so much as a calculated effort. If there’s one thing I’ve learned writing about craft beer, it’s that you probably need to take brewery origin stories with a substantial grain of salt. Hooper’s Hooch, incidentally, moved 2.5 million bottles a week at its peak in the UK. That’s 429,000 HL a year during the height of the late 1990’s alcopop craze.

1995

Canada can be a very staid place, and until 1995 there were significant regulations in terms of the ability to advertise alcohol on Television. The CRTC allowed beer and wine below certain percentages of alcohol to be advertised, but banned liquor regardless of its strength. As Clayton Ruby pointed out in The Toronto Star (18th Jan, 1995), freedom of expression was denied to distillers and was ruled unconstitutional. By September 15, 1995, the CRTC eliminated “ the effective prohibition against advertising for spirits-based beverages containing more than 7% alcohol by volume, and rendering advertising for these products subject to the same regime as that applicable to beer, wine and cider.”

Now, the current version of Mike’s Hard Lemonade contains 5% alcohol. Originally, though? 6.9%, meaning that the product was in development prior to the amendment of that regulation.

When Mike’s Hard Lemonade is introduced in 1996, it has two major things going for it: Product Novelty and a new advertising medium. You might reasonably ask whether the new advertising medium did anything for the sales of spirits.

Yowza.

1996

It’s not immediately evident that Mike’s Hard Lemonade is going to be the breakout star of the RTD category based on reportage from the era. LCBO newspaper advertising has it alongside Seagrams and Bartles and Jaymes berry flavoured coolers. It may be the new thing, but it’s not remarkable in and of itself.

That said, it’s obscured somewhat by the aforementioned alcopops. Maclean’s Magazine features an article entitled Pop With Bite in December of 1996, outlining some of the competition. International sales are expected to amount to $700 million in 1996, and Hooper’s Hooch, the UK Brand is being produced under license in Hamilton, Ontario at the Lakeport plant, which will at some point produce every single top selling alcopop in the province. They are distributing to Quebec and are gearing up for the Northeastern United States. Bill Sharpe who runs Lakeport at the time claims that it is “the most successful launch of a new beverage product in a decade.”

The Macleans article does point out one thing that gives Mike’s Hard Lemonade an advantage. The majority of these beverages are 4.5% alcohol. At 6.9%, Mike’s is comparatively concerning to watchdog organizations. In fact, earlier in 1996 in British Columbia, the provincial liquor board dug in its heels about the branding of the product. Bob Simson, who is the manager of the BC Liquor Board at the time, wants the label changed to read Mike’s Vodka Lemonade despite the fact that the brand had already been approved federally. The concern is that young people will not be aware that the product contains alcohol if the label says “hard.” It would later turn out that the board had exceeded their jurisdiction in the attempt.

Eric Appleby, of the UK based Alcohol concern is quoted in the Maclean’s article saying “It’s hard to see how these drinks are not meant to encourage young people to start drinking younger and younger. I wonder when they will bring out a bottle with a teat on it.”

The moral issue of alcopops, rather than the quality of the beverages, becomes the defining characteristic of reporting on the subject right up until the lifestyle and business columnists get a hold of it later in the decade.

1997

While the RTD and alcopop segment continue to grow, no one seems to show very much interest in the topic in the Canadian press. As a growing segment with comparatively little variability, there is, perhaps, not much to say. At the same time, brewers are still battling over ice and dry specialities.

1998

Michelle Shephard, writing in the Toronto Star on April 19, 1998, clutches pearls magnificently: “It looks like lemonade. It tastes like lemonade. But you won’t find it for 10 cents sold by little pigtailed girls at street lemonade stands. And it won’t take many of these drinks to make it a night you won’t remember.” Shephard is an education reporter, and you might have hoped she’d understand reverse psychology. She quotes the following figure, without a source: 11.5 million litres of spirit based coolers sold in Ontario between April 1, 1997 and the end of February 1998. Sales are up 80% year over year to probably something like 125,000 HL if you assume March 1998 is comparable to the previous months.

Shephard interviews two female Ryerson students who are quoted as saying “we went to the bar downtown and just decided it was a night to drink Mike’s. We had one then oh, this is gone. Then, oh this one’s gone so let’s get another…” and “They’re just so easy to drink you don’t even know you’re getting drunk.” One feels as though this might have backfired somewhat.

It’s around this point that Hooper’s Hooch and Two Dogs fall away in the Ontario market. Mike’s has the advantage of being Canadian owned and therefore possessing a more intuitive grasp of the market. It’s the number one product in the LCBO’s RTD category in 1998 and it’s spawning a wave of imitators. One of them is called Joe Hard Lemonade, which one assumes is the kind of off brand cash in the Simpson’s writers room would think was too lazy to be a joke.

Mike’s Hard Lemonade basically revitalizes the 80’s throwback cooler section of the RTD market as well, with Bacardi launching products called Extreme, Big Bang and the Original Stiff. Graydon Lau who is in charge of Bacardi’s lineup is quoted in Marketing Magazine in October crediting Mike’s with attracting male drinkers, and had studied what made Mike’s “socially acceptable for a guy to be seen walking around with,” concluding that it is an androgynous product. The original coolers had slender bottles and were clearly being marketed towards women, and, according to Lau, 90’s women were not interested in being marketed to in that way.

Paul Brent has the following headline in the National Post in December: Molson Helps Guys Drink Lemonade: Puts Arctic Brand in Brown Bottles to Comfort Men. “If you like, your buddies can think you are drinking a beer” the director of marketing at Molson is quoted as saying. In regards to Labatt’s Boomerang, the senior brand manager at Labatt Quebec is quoted as saying, “We were aiming this at people who don’t like the taste of beer. It’s a little bit more feminine.”

Male fragility is responsible for a significant portion of Mike’s Hard Lemonade’s success. Bloomberg reports the following quote from Anthony Von Mandl in 2006: “25% of guys didn’t particularly want to drink beer, but couldn’t be seen holding anything else in their hand.”

1999

Reporting changes a little here, triangulating between the success of the initial product, the imitators of it, breathless business reporting and steady caution on the part of watchdog groups. That’s because it’s now a full blown trend with established players. This is also the year that Mike’s Hard Lemonade launches in the United States, making it an international concern.

May 24, National Post: Paul Brent has an article about the first advertising campaign. It’s remarkable that Mike’s has managed its market dominance without having done that already. Consider the amount of worry about young drinkers when they weren’t even really being advertised to. The ads are seemingly not on youtube, but are Mulder and Scully influenced, making them the most 90’s thing possible. The article reports three important facts: Mike’s Hard Lemonade has 91% market share, worth approximately $50 million dollars. They are spending $6 million on advertising on TV and billboards. The tagline is “an excellent source of vodka.”

Paul Brent can’t wrap his head around the fact that 60% of the customer base for Mike’s is male, as reported by the Mark Anthony Group, reporting instead that the “saccharin sweet booze has cultivated a devoted core of young female partygoers.”

June 25, Canadian Press: “For the first time in a decade, thirsty Canadians have boosted their intake of spirits… Last year, Canadians purchased 138.3 million litres of spirits, up 6.3% from 1997… The substantial increase in Canadian spirit sales was largely due to an 80.9% increase in the volume of domestic based coolers.”

July 3, Globe and Mail: Seemingly for the first time, someone is taking the category seriously. Doug Saunders at the Globe and Mail actually puts together a taste test of the hard lemonades available with the control being a stoli-laced snapple. Unsurprisingly, Mike’s does very well, although not quite as well as the Captain Morgan version, in a foreshadowing of things to come.

July 18, Toronto Star: Vinay Menon is a pop culture reporter. Compare his opening salvo to that of Michelle Shephard’s in the same paper from the previous year. “As the room spins and the vodka vice clenches mercilessly around your dehydrated internal organs, the last thing you taste is lemon. And as a rush of saliva coats the back of your throat and you crumble awkwardly in front of the porcelain god, you find yourself damning Mike.”

It’s a little over the top. The article raises concern about underage drinking and the fact the marketing does likely spill over into an under 19 demographic. It quotes a 19 year old who has been drinking for four years as saying “The stuff tastes so good that people drink it faster and then get drunk faster.” The article also provides the information that LCBO spirit cooler sales in fiscal 1998-1999 are $81 million, representing 16 million litres. Mike’s Hard Lemonade represents 60% of volume sales.

December 18, The Globe and Mail: Just in time for Y2K, The Globe and Mail puts together unflattering caricatures of Toronto Trend Followers. Mike’s Hard Lemonade would be the drink of choice for the habitually hip. I’m pretty sure I know the guy on the left.

This is the peak of mainstream appeal in Canada, if not sales worldwide. At the point where you’ve spawned imitators and continue to dominate the segment anyway, you’ve made it.

2000

March 16, The Globe and Mail: Seagram’s is attempting to launch a product in the United States called Rick’s Spiked Lemonade. They are sued by Mark Anthony Brands on the basis of trade dress. Mark Anthony Brands projects sales of two million cases in 2000, but it is unclear in the article as to whether that is solely in the United States.

June 8, Toronto Star: William Burrill (described at the time on the quill and quire website as being nearly as two-fisted and dangerous as Hunter Thompson) writes just an abysmal piece of dreck with the typical Canadian hoo-ha equating beer drinking to manliness and getting angry about nothing for man points. I can’t believe he got paid for it. On the other hand, it does illustrate that the RTD cooler segment is far enough into the mainstream to have attracted the attention of lame old white guys.

Later in the summer, the Star will run a top 10 coolers section in another section. Mike’s Hard Cranberry is listed, meaning that the brand is diluting. After you’ve hit the mainstream, you need to keep the sale figures up.

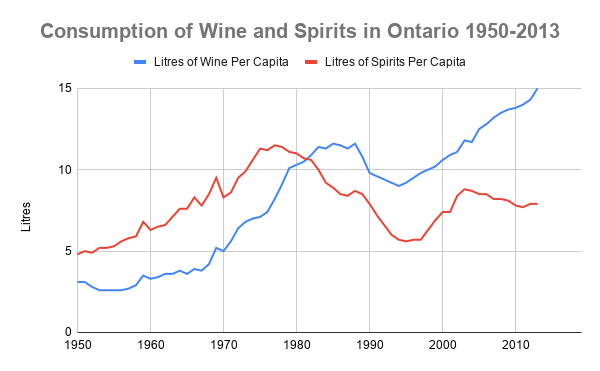

June 24, The Globe and Mail: A simple graphic runs, detailing the previous year’s statistical consumption. It’s helpful for visual learners.

2001

April, Canadian Packaging Magazine: Teresa Cascioli, current head of Lakeport, has shepherded the company back from the brink of bankruptcy and has been announced as one of a handful of facilities to produce Smirnoff Ice, which is an RTD blend of Smirnoff Red vodka and citrus juices. This moves Lakeport to seven day, three shift production.

August 4, The Globe and Mail: No less a critic than Beppi Crossariol is legitimately reviewing coolers in the Globe. The article titled, “Coolers: The Shape of Things to Come,” gives quite a good overview of the situation. There are 75 RTDs in Ontario, 53 of them vodka based. He says shipments are at “8 million-nine litre cases a year and are growing at about 15 percent a year.” That’s about 720,000 HL nationwide.

Mike’s Hard Lemonade is down to 42 percent market share, despite a new slogan: “Grab Life By The Lemons.” The category is being diluted by drinks like Rev. People are starting to get very overconfident. Paul Meehan, who is director of marketing for Mike’s says that the RTD cooler market could expand to 50 million cases a year. That would be 4.5 million HL. That would be a fifth of total beer volume in Canada. Mr. Meehan is on the top of a wave at the time so you can excuse it.

Smirnoff has an advantage over Mike’s. Name recognition from an alternate sector of the market. At the time, there is also a push towards premium vodkas happening, and this product slots neatly into that ongoing trend. Beppi awards it his highest marks in the column, giving the hot new thing a leg up critically. Does that matter? It makes a difference in that it will get people to give the new Smirnoff Ice a try.

December 19, The Globe and Mail: The Beppster continues: “The category that Mike’s Hard Lemonade built is going stronger than ever thanks to the launch of Smirnoff Ice and premixed Mott’s Bloody Caesars. They’re cocktails for people who want to be seen clutching a label. So watch for more big companies to muscle their way into the category with brand extensions. Can Absolut Lemonad be far behind?” Prescient. Absolut Cut would turn up in the near future.

2002

Things are slowing down. There is no talk of moral repercussions. One good indicator of how hot a trend is going to be is how early in the year it shows up in media.

June 23, The Toronto Star: Douglas Cudmore’s column titled “Try a New Sip This Summer” illustrates the sheer number of players in the RTD category. The new products are Canadian Club and Ginger, Bacardi Silver, Mike’s Hard Orange. Tabu Forbidden Fruit is given a shout out for its packaging. For a column meant to entice you to novelty, it’s not very exciting tonally, and points out that the Mike’s Hard Orange “doesn’t live up to its predecessor’s standard, with a weak texture and almost bitter taste.”

June 28, The Globe and Mail: We’re not interviewing 19 year olds anymore. The column “Spirit Coolers Proving hot” is interviewing a 28 year old woman and her 34 year old friend. John Heinzl helpfully provides us with the information that Sminoff Ice is now in the number one spot according to Spirits Canada. The LCBO’s spirit cooler sales are up to $137 million for the 2001 fiscal year, up from $85.2 million.

Steve Doyle, a Diageo brand manager says of the marketing “There’s no doubt about it. We’re targeting beer drinkers and trying to provide them with an alternative to beer.” That is borne out by Molson and Labatt’s moves at the time.

Stephen Beaumont, noted beer man, says “It’s the flavour of the moment… Five or ten years from now it’ll be something completely different that will be the new thing everyone is talking about. We’ve seen this before with wine coolers.”

August 21, The Toronto Star: Two months later, the Toronto Star interviews a different 28 year old woman. “In Canada, cooler sales have nearly tripled in the past five years, and there’s no end in sight to their meteoric rise in popularity.”

Paul Meehan, still marketing director at Mike’s says “Smirnoff Ice is about style and fashion. Our ads don’t have people at super stylish parties, or people trying to sneak into them… parties where guys are carrying purses and spend half an hour on their hair.”

Considering the earlier insight held by the company, a bit of an own goal. The article ends interviewing a 26 year old man: “I remember my first one. I was at a Leafs game and since then it’s just sort of stuck … Beer is really bitter but Smirnoff ice has a kick to it. I like it because it’s fruity. I know that sounds bad, but it’s true. My Buddies will sometimes jokingly say I’m drinking a girl’s drink. But it’s way stronger than beer.”

2003

No critical coverage of the brand to speak of.

Aug 9, The Globe and Mail: In an article entitled Molson Regional President Steps Down, there is a mention that Mike’s Hard is being packed at Lakeport. With it’s popularity lagging, Lakeport begins to market its beer at a significant discount in order to make margins work. Yes, that’s right. Mike’s Hard Lemonade’s failure is laterally responsible for Buck a Beer. Their beer had been something like 32 dollars a case up until that point.

2004

May 22, The Globe and Mail: Beppi Crossariol includes a cursory throwaway mention of Mike’s Light on paragraph 25 or so of his column. He says it includes aspartame. He does not include tasting notes.

It’s over.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN

Actually, the question is what did the Mark Anthony Group learn? There are things that we can glom onto here to understand hard seltzer and where we stand with it.

One thing is that Anthony Von Mandl was extremely correct in his assumption about the fact that 25% of people didn’t really want to be drinking beer just because the situation called for it. I ran a poll on twitter asking people how they felt about Mike’s Hard Lemonade at the time of its release and it turns out about 27% of people actually enjoyed it. I assume that that is more to do with major brands than craft beer which has many options for different flavours.

If you take Mike’s Hard Lemonade as an artifact, part of its success is the packaging, which is non gender specific. It’s a clear bottle that looks like a beer bottle. Consider White Claw for a moment. In Ontario, at the very least, it’s in 473ml cans. That makes it identical to the majority of craft beers and RTD segment products. The branding really only changes colour between flavours.

That’s another point of interest. With Mike’s Hard Lemonade, each additional flavour diluted the brand. With White Claw, they’ve introduced all of the flavours at once, meaning that the brand is somewhat immune to that dilution. Some may be more popular than others, but it’s not as though competing companies can make different flavours specifically to stand out. It’s a bit of a hydra.

People level the criticism at mass produced beer that it’s meant to be as inoffensive as possible in order to reach as wide an audience as possible. Well, White Claw does that. This is a product that is low carb, gluten free, comes in a variety of simple popular flavours, does not seem to market to a specific demographic in the way that alcopops did.

We’re already well into the imitators phase of the trend. I think the issue this time around is that larger beer brands are more willing to dilute their own brands in order to compete instead of creating individual labels, not that they aren’t doing that as well. White Claw currently has 60% of the US Hard Seltzer market. That aligns with the 1999 figure for Mike’s Hard Lemonade, prior to its decline.

The problem is that drinkers continue to be fickle. And it would seem that the trend cycle has sped up somewhat since 1999. I keep coming back to the hipster caricatures in the Globe and Mail. If I were to ask you for three other details about who you think is drinking White Claw, you’d be able to give them to me very quickly. That’s the peak of mainstream popularity. It’s downhill from here.

I always find it interesting that Mike’s in Canada is vodka based but in the US it is a malt based beverage.

And even though I love beer I occasionally drank Mike’s in the 90’s. Even though I grew up on the west coast and there were a lot of beer options available even back then.

Pingback: The Nights Have Gone Cool But Thursday Beery News Notes Go On – Read Beer

Pingback: The Days May Grow Short When You Reach September, Frank, But There’s Still Time For Beery New Notes – Read Beer