I’m not quite sure how I ended up on the radar of George Brown College. I know Troy Burtch from Great Lakes had been teaching their continuing education beer appreciation course, and he probably recommended me, given that Jesse Vallins had a scheduling conflict. It was timely. I had finished the second edition of the Ontario Craft Beer Guide and found myself at something of a loose end, taking on contract work to feed the cat.

That was two years ago now; time which seems to have flown by. At the time, I was glad for any work related to the subject matter I’d spent more than half a decade on. It may have been the same week that I started leading walking tours for Toronto Urban Adventures; that was something of a doddle as well, given that it was based on a book I had written.

You have to understand that until I was about 34, I was absolutely terrified of speaking in public. I once MC’d a friend’s wedding with my hands shaking so badly that the mic I was holding created a sort of doppler effect in the room as it jittered and twitched back and forth in front of my mouth. I must have looked like a gorilla in a tuxedo in an earthquake.

That changes relatively quickly when you suddenly find you’ve got to make a living from talking to groups of people. The secret is this: They want you to succeed. It’s easy to confuse attention with scrutiny, and if you’re of an anxious disposition to begin with, well, the microphone is going to handle like a cobra.

It didn’t really occur to me that I might be good at teaching people things. I had never taught anything except brass instruments at a summer camp when I was 17. Nevertheless, there I was the week after the interview having acquired whatever slides and material existed for the beer appreciation course. It had been through a number of instructors over the years, with some illustrious Ontario names: Stephen Beaumont, Paul Dickey, Ron Keefe. People who knew what they were talking about. I imagine they all changed the content around to suit them, and you could sense a little influence from each camp. In the case of Troy’s tenure, the course ended up featuring Great Lakes a little heavily. This is a not a bad thing, but certainly emblematic of the extent to which you could customize the content.

Based on early conversations with some of the previous instructors, I realized that this was not set in stone. It was also pretty obvious that we’re in a great place at the moment in Ontario for diversity of beer styles in the LCBO. That’s probably the work of Mark Wilson, Neal Boven, and John Tyler over at the LCBO who are trying to make sure there’s a good one of everything. Imagine trying to put together a week on North American craft beer styles in Ontario in 2004. It’s no wonder Stephen Beaumont had a week on wheat beers; we had access to them and very little else.

The idea, fairly early on, that we were going to create a whole Beer Specialist certificate seemed a little daunting. The only comparable thing in Ontario is Prud’homme, and I’m largely unfamiliar with the content of it, despite having had Roger Mittag for sensory at Niagara College. Niagara College is for brewers, not front of house. Cicerone is really just a series of exams, and while there’s a syllabus, it’s on the individual to fulfill it.

How do you create something unique from scratch? For one thing, it’s continuing education, which means that it’s nights and weekends. It has to be affordable. It’s a self selecting group of students and they have presumably been through a long day at work or a long week at work by the time they get to you. It has to be instructional, educational, and entertaining enough to hold their interest. It probably needs to be a little interactive and there has to be room for discussion. That goes for all 67 hours of class time from the preview workshop to the last week of the last class.

So there I was: anxious about public speaking, with no experience teaching, tasked with creating and administering 67 hours of content, and just bloody minded enough to think I could pull it off.

After all, you gotta feed the cat.

It’s amazing how far you can go with an understanding of narrative structure.

Sitting down with the slides for the Beer Appreciation class two years ago, I found that it was sort of arbitrarily delineated, but it made sense from a certain point of view. If you were designing such a course more than a decade ago, as Stephen Beaumont was, you were significantly constrained by the things that actually existed in the market. Remember, the uptick in breweries in the province didn’t start until 2007 and didn’t really catch on until 2010. I’ve talked to Stephen about this and I think I’m right in saying that he couldn’t possibly have done much more with the selection of beers to hand. In that sense, just starting a decade later handed me a significant advantage.

I don’t know what changes which people made to the class over time; it’s a little like a game of broken telephone. When I inherited it, there were weeks on ale, lager, wheat beers and Belgium. Again, from a certain point of view, it made sense. If you were, for example, a master BJCP judge like Paul Dickey, that would allow you to break things down into stylistic guidelines based on larger families. That wasn’t going to work for me.

I rearranged the six weeks into brewing traditions. Subsequently, talking to Bill White, I would learn that he had the same inclination when he was doing education for Labatt in the 1990’s. I really want to get him on some kind of podcast format about it in the near future. It’s fascinating listening to him talk about it.

The thing is this: You can teach people about beer styles, but for the purpose of retention, it’s good to have a narrative framework to hang that on. There’s the introduction week, where we explain the basics of tasting and assessment, the concept of styles as being historically and culturally designated, and the basics of ingredients and processes. You can work historical subtext into the material. Germany is as much about technological development as it is about that meandering journey from Bock to Helles. England is as much about governmental controls as it is about Cask Bitter and IPA. Belgium’s iconoclasm is as much about cultural identity and its reclamation as brewing. There’s finally enough American craft beer in the LCBO to be able to run all three of those narrative threads through the journey craft beer has taken the last 40 years.

And what about the modern era? You can’t test people on current trends, but you can certainly show them off. You’re training people to be able to talk about what’s happening in the market. The subject is “Beer,” not “Beer until 2010.” I’m throwing trends from the last five years at them after the exam so they have some explanation of what’s happening currently.

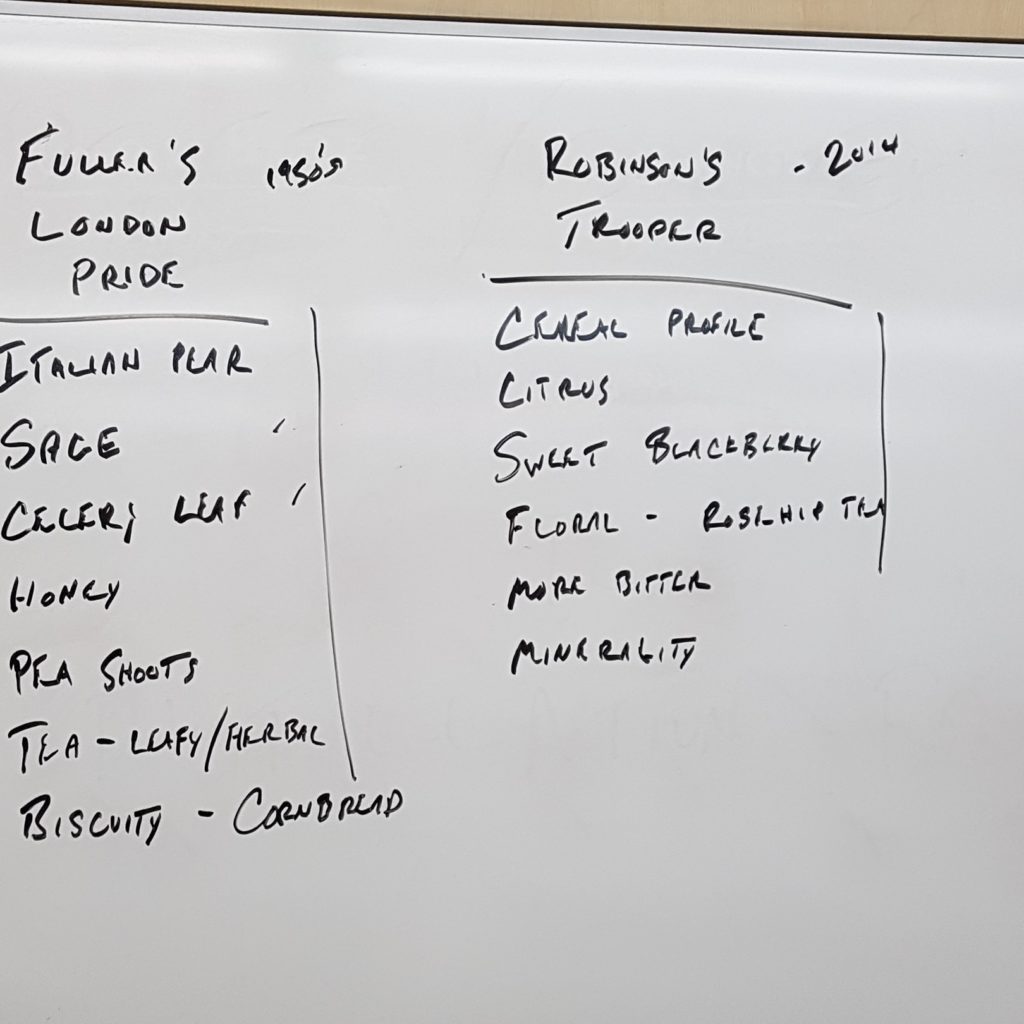

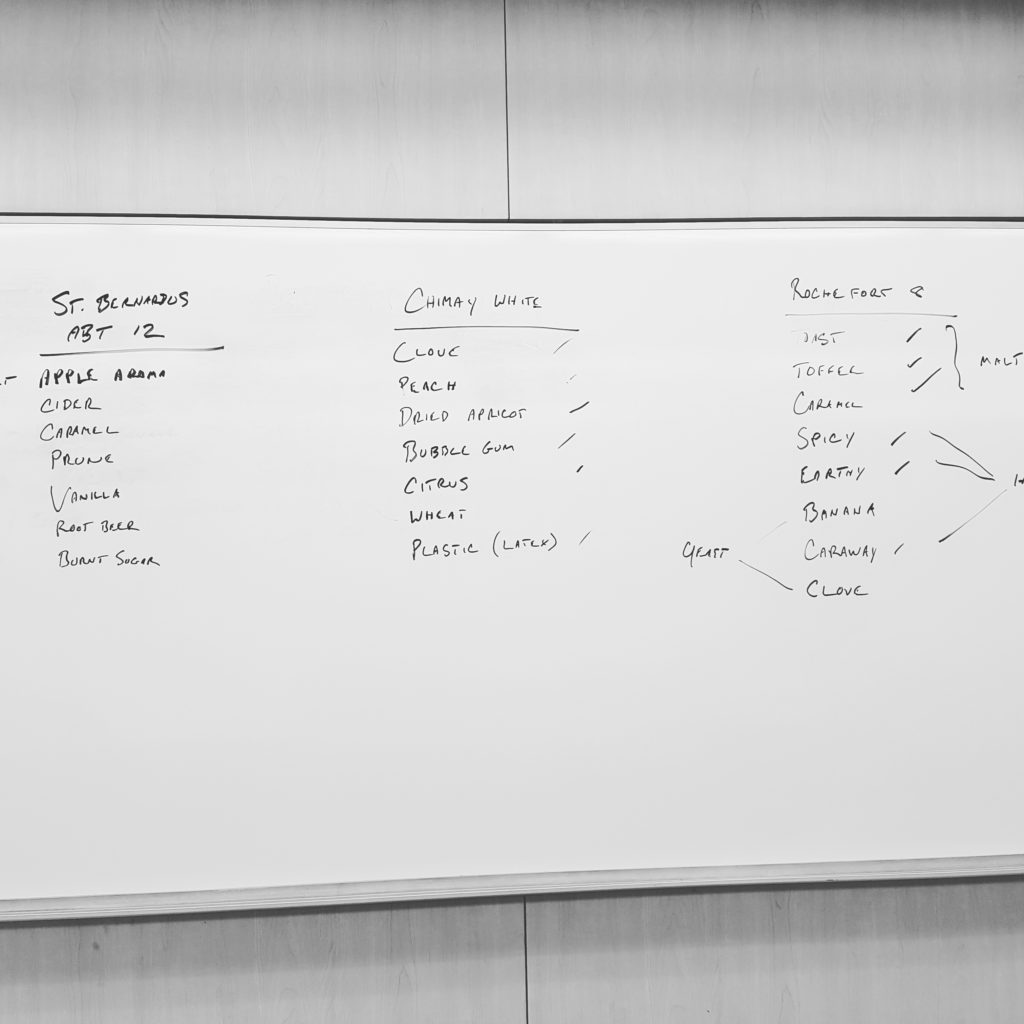

I’ve aimed for something more socratic and less prescriptive from a pedagogical standpoint. I want the students to come up with tasting notes for the beers from the jump, and while I caution them to be fairly positive with the descriptors, I find that the communal aspect of putting tasting notes together for each beer is beneficial to everyone because it fosters a sense of involvement and helps develop vocabulary. Palate might be 30% vocabulary. I find that by about midway through week four, nearly everyone is talking sense. You can feel it click in somewhere around the St. Bernardus Abt 12.

In terms of maintenance, this setup requires a little vigilance. I have found that the North American section is a moving target. I once included Smuttynose Robust Porter and then six weeks later found that they were at auction. Breweries sell and will continue to sell. Sometimes they say stupid things on social media or have bad policies and have to get switched out. It’s also the case that some styles from all weeks of the course come and go from the LCBO, so I have to keep an eye out for cases of product that we can snaffle up and cellar. It’s good. It forces me to keep it current up to the day I’m teaching it.

Beer I contains something like 60 beers over six weeks.

It’s a project for the next month or so to hone the material a bit. The last eight months have been about development of the other two courses.

If I had a do-over, I’d have rewritten the current catalogue description for Beer II. It sounds like it is an extension of Beer I, but that is not really the case.

Beer II is about flavours and where they come from in beer. It’s the kind of thing that I never saw addressed very much and in designing a new course from scratch, I thought it was the kind of thing that people would be interested in. On every brewery tour you’ve ever been on, they’ve got little jars of malt and hops on the bar, but if you crack those open the hops will be cheesy and the malt will be stale. It does it a disservice. I’m trying not just to talk about ingredients, but stay cutting edge with it.

While we talk about different malt treatments in Beer I, this is a massive expansion. We’re talking about kilning methods and tasting simple steeped wort alongside beers whose malt profiles are actually made up of those ingredients. Of course you get the basics of enzymatic modification and all that along with it. Same with hops. I think we did six varieties of hop tea and companion beers that use them along with an explication of isomerization and bitterness and the different flavours and aromas that exist when you’re more gentle with the terpenes.

Obviously, you need to talk about yeast, and we’re reading yeast spec sheets while tasting the beers those specific strains make. Some breweries were very helpful in coming forward with that information. We’re basically doing Lager, English Ale, Hefeweizen, Belgian, Kveik. Least phenolic to most. Most tame to least domesticated.

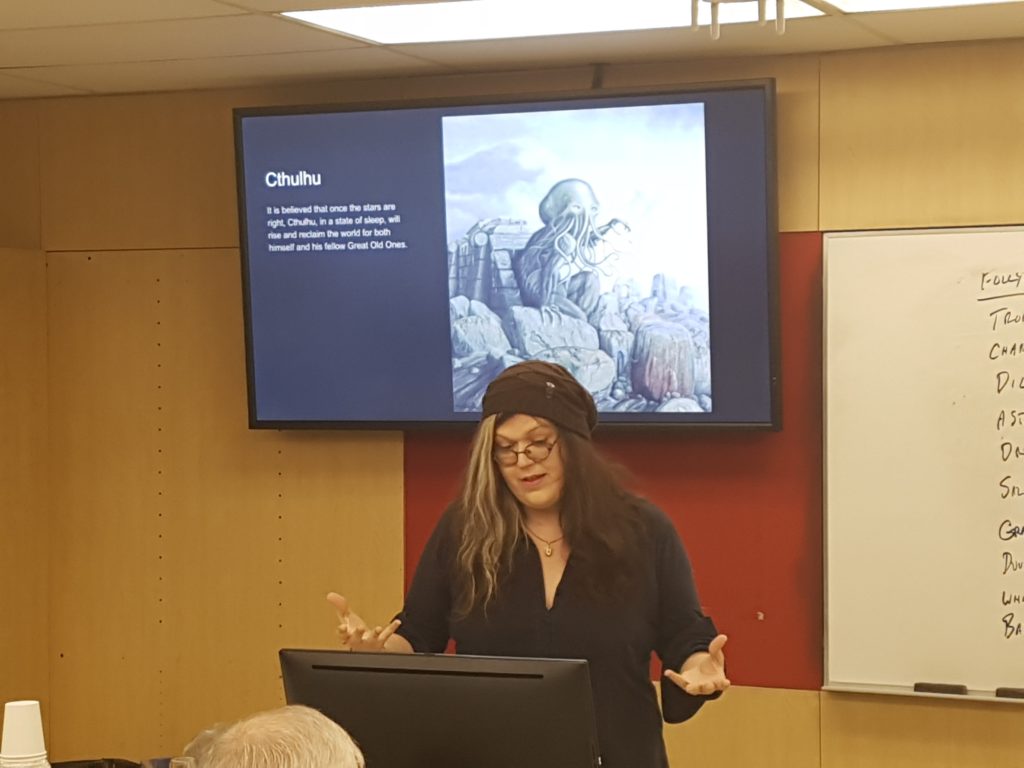

If you are going to talk about recipe design, and you’re going to talk about Sawdust City’s Blood of Cthulhu, you obviously need to bring in an expert on Lovecraft.

Then we use that information to design a recipe. Now, you can’t let a class of 20 people try and come to consensus on a recipe, so I’m trying to include a gimmick. This semester it was that it had to feature Alsatian hops since I had been to an Alsatian hop rub. With a smaller class, we came down to a Lithuanian Farmhouse Ale with Barbe Rouge, Triskel, Aramis, and a Strisselspalt dry hop. Last semester, I designed a milk stout based on a vote on style and based it thematically on George Brown’s Bow Park farm in Brantford, Ontario from the 1870’s.

For week three, we actually brew the recipe with Toronto Brewing.

For week four, there’s a cursory section on water, and lengthier information on packaging and draught. Sometimes we’re able to work in a field trip to look at a draught system.

Week five is an off flavour seminar. We’re using the Siebel intermediate kit for this, which has 12 off flavours. Since it’s most people’s first experience with that, we’re doing them significantly above threshold for dilution. I think with a smaller class we might do an initial aroma pass above threshold and then dilute to aim at individual sensitivity. You can customize these things with a little thought and some mis-en-place.

For the final exam, I am making them evaluate their own beer and tell me what’s wrong with it. It’s not that we’re screwing up the beer intentionally, but on a group experience homebrew there are probably going to be flaws. Whether it’s an off flavour or simply a correction to the recipe that would improve it, I’m getting the students to tell me everything they can about the liquid in front of them. Basically training them to diagnose it down to individual components. Ideally, by the time they get out of Beer II, they understand where all the flavours are coming from; in some cases with chemical derivations.

Beer II contains a smaller number of beers, but all suited to an exacting purpose. And of course, there is a custom beer. It might be something like 20 in total, if you include Amsterdam 3 Speed, which we use in quantity for the off flavours.

I have a complicated relationship with food. You may have noticed that I cut a somewhat Falstaffian figure; ie. could stand to do a sit-up or twelve. You may also have noticed up top there that I make mention of having to feed the cat. Writing about beer is not a particularly lucrative career, and as a result of it, I have a party trick I can perform: I can tell you whether your beer’s grist is above 5% caramunich malt based on the extent to which it tastes like dried red lentils. I had a year where I ate enough of them to be able to do that.

Maybe it’s the result of that little bit of privation that informs my view of the Complex Beer Pairing course. I’ve talked with my co-author Alan McLeod about this over the years, and I think there is a tendency for people to take the ability to pair a beverage with a meal for granted. Alan’s gran was a cook for a stately home in Scotland. Pairing is second nature to him, but as in most things, Alan is sort of an outlier.

I didn’t want to rely on the tricks that I usually see for beer and food pairing because they’re so extremely bourgeois. Consider it a moment: How many times have you seen people extol the virtues of beer and cheese going together? I know, for example, that when the cicerone program was working with grocery stores last year, they were recommending specific cheeses to go with beers. As an informational resource, you don’t want to try to immediately upsell people.

Let’s say you walk in off the street and you are just looking for a beer. You don’t know a lot about beer, and you are learning that discipline. Well, cheese is an entirely separate discipline! The onus is suddenly being placed on people to know about European heritage and the difference between various types of milk and dairy production and fermentation. Not only that, but they’re meant to choose good artisanal cheeses that cost a bundle. And this is the starting point? I’m not saying that they don’t go together, but consider the gatekeeping quality there. It’s like listening to someone explain the rules to a board game.

I’m going to bet that same person eats non-cheese food, which is, incidentally, about 99% of food. I thought it might be a good idea to hedge my bets and go with that. Why not meet people where they live?

That’s important. For the purposes of Complex Beer Pairings, I erred on the side of inclusivity. There are vegetarian and vegan recipes included and things from different cultures around the world. My thinking is as follows: We live in Toronto and it has everything. You can get any kind of food you want. We’ve got people from all different backgrounds living here and it would be great if we could share beer with everyone instead of just lactose tolerant middle class folks who have enough time to think about washed rinds and blue veins. I wanted different cultures represented and I wanted different economic backgrounds represented and I wanted it to be fun and inclusive and diverse.

We’ve separated it into Snacks, Brunch, Lunch, Dinner, and Dessert. We’ve got all manner of great stuff. I’ve got dishes from Vietnam, Southern California, Italy, Egypt, Israel, England, Belgium, Germany, Jamaica. We’re essentially starting with classic beer cuisines and seeing if we can extrapolate rules from them to apply to international stuff that developed outside of proximity to European beer culture. I’m thinking about ways to make it a little more international while retaining the balance of vegetarian options. The dessert week, in and of itself, is nearly worth the price of admission.

We’re doing the initial run through and it has been instructive. By week four, everyone is anxious to play around with the pairings, so I’ve been letting the class choose which beers to try with which dishes, although the initial impetus was logistically inspired. One week during inventory for the culinary school, Chef Ian Dowsett ended up improvising the dishes for the class. Se Debrouiller. Initially, that was terrifying, but ultimately it proved valuable in the sense that if this information is going to translate to a student’s day to day life, it’s just as effective to be able to think on the fly as it is to plan ahead. It will make the course more practical in the long run.

We work up a flavour profile for each beer and then talk about why it works or doesn’t work with the dish. It’s basically a license to play around with ingredients and recipes and ideas; something that doesn’t really exist in day to day life. It’s more effective as a six week boot camp on how to think about pairing rather than as a prescriptive series of do’s and don’ts. When in doubt, I try to foster independent thinking.

I’m pretty sure there are 50 beers in Complex Beer Pairing over five weeks, with a sixth week for presentations. There are two assignments. The main one is to pick a beer out of a hat and come up with a complex pairing for that beer and present it. The second is budget conscious: armed with 15 dollars, pair a beer and a snack and submit photos, justification and receipts.

Judging by the number of receipts from NoFrills, I’m pretty sure I took the right tack on the material.

Looking back, the thing that astounds me is how good a value the Beer Specialist Certificate is. Beer I is currently listed at $254.00. Beer II is listed at $279.00. I’m not quite sure what the price point is on Complex Beer Pairings as there isn’t a segment scheduled for the Spring Semester, but the students tell me the entire Certificate start to finish is something like $900.00. For context, that includes something like 130 beers to taste, a beer to brew, and five weeks of dinner. We may change it around a little, but it’s a phenomenal value. It will only improve, as I intend to continue working at it.

The other thing I want to point out, having talked to Ren Navarro from Beer.Diversity while designing the certificate, is that I’m appreciative of the fact that craft beer can be a pretty hard industry to crack because of the demographics of the market. I’m trying to make this as approachable as possible to remove some of the gatekeeping elements from the content. If you’re thinking about transitioning to the craft beer industry and you don’t know how to do it, this is a great value and therefore pretty low risk. We even have a workshop if you’re looking to test the waters before jumping in.

I’m relatively sure that we can get a student from knowing nearly nothing about beer to being able to hold a conversation about nearly any aspect of it in 18 weeks, and for less than a month’s rent in Toronto. It would probably qualify people taking it (with a little independent work) to go for their BJCP or the first two levels of the Cicerone program.

I suppose the other upside is that I tend to have my ear to the ground on employment opportunities and might be able to help students find employment. Obviously, that depends on the opportunities that exist at the time, but it’s something I’m happy to do.

After all, you also gotta feed the cat.

I’ve been wanting to take beer appreciation at George Brown for a couple of years but sadly haven’t managed to get to it. But after reading this post I’m definitely in this fall! Looking forward to tightening up my beer knowledge!!

Pingback: The Thursday Beery News Update For Fire, College, Style and Being Fifty-Six – Read Beer