If we can establish a popular mood at the turn of the century in Toronto as it regards the labour movement during a period of rapid population expansion, we’d do well to look at the Toronto Star from March 23rd, 1901. The week’s labour column speaks not only of the general council, but of the Patternmakers, Machinists, Metal Mechanics, Bakers, Musicians, Coal Drivers, Longshoremen and Cigarmakers. Damned near everyone unionized before the brewery workers. However, it’s the Horseshoer’s Union label update where the first mention of brewing unions crops up:

As perhaps it would not be quite convenient for you to attempt to pick up the foot of every horse driven to your door in a search for the stamp of the label under the heel of the iron shoe, the union horseshoers themselves will take the means of such merchants and traders as have adopted the union label for their horses. At the regular meeting of the Horseshoer’s Union this week, the committee having the matter in hand reported the names of several of the largest firms in the city, including brewers, butchers, and bakers who patronize the union label. Members of organized labor will yet make sure that even their beer shall have been drawn from the brewery by a union shod horse and brewed by a union brewer.

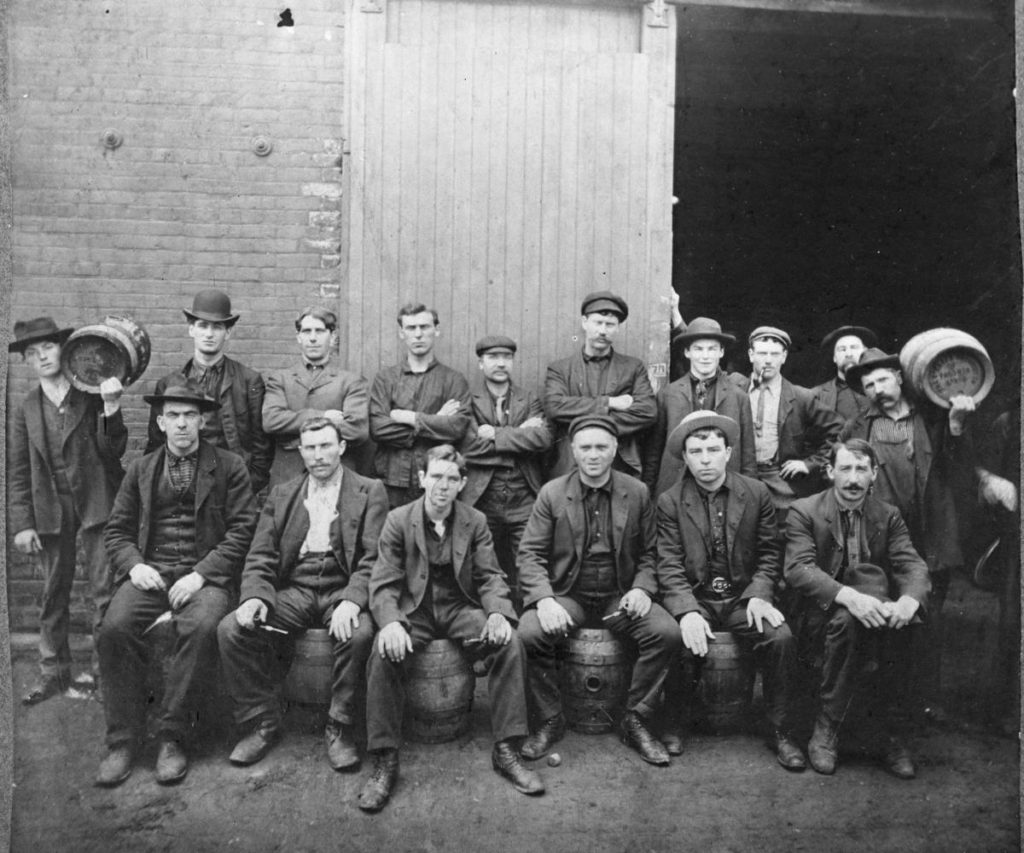

There’s a spirit of solidarity at the time that is more or less unthinkable today. Realistically, the brewing industry was behind the times at the beginning of the 20th century. This is possibly due to the fact that organization is hindered by the nature of the employment. If you’re paid something like six dollars a week for sixty hours worth of work and you’re constantly plied with beer, sober second thought about organization might be thin on the ground.

Consider for comparison the Maltster’s Union, which managed to organize prior to the brewery workers, potentially for the reason that the number of discreet performed roles was smaller. This, from November 13, 1902:

The Maltster’s Union met last night to consider the reply of the breweries to the demand for an increase in wages. The men asked for $10.50 per week. The employers make a compromise offer of $10 per week, with the provise, however, that 50 cents per week off the $10 shall be retained in the hands of the employer, to be paid over in a lump sum at the end of the malting season, conditional on the good behaviour of the men.

The union expressed its willingness to accept the compromise offer of $10, but emphatically rejected the provisional clause. On the whole, the reply of the brewery firms was considered a favorable one, and the feeling is that the difficulty will be settled without serious trouble.

As brewery jobs go, malting is comparatively skilled labour, and since the breweries of the era typically malted in-house, there’s a clear choke point in terms of production here. The job is also further removed from the brewing part of the business so may not have had quite the same access to the cellar.

One thing that has not changed much since 1902 is that despite the presence of social media, change happens in real time on a human scale. While the Maltsters are already organized, the Brewery Workers Union is nascent, somewhere in its second month. October 6, 1902:

A new union was organized on Saturday night in Richmond Hall, when a well-attended meeting of brewery employees was held, in response to the call of the organizer for the United Brewery Workers of America, an international union which has grown very strong in the United States within the past year or two.

It’s very likely that there would have been rumblings within the breweries of organization. In point of fact, the Toronto brewers of the 19th century as personages had pretty largely moved on from that initial business by this point. The Dominion Brewery was in the hands of a British consortium, Robert Davies helping oversee his son’s brewery at Copland. Alexander Manning, ex-Mayor and owner of Toronto Brewing and Malting passed in 1903 (reported next to a story titled Monkey War at Riverdale Zoo):

The will directs the trustees to sell and dispose of the premises and business of the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company at the earliest practicable moment at which a sale can be reasonably effected, even at a sacrifice; “and I authorize them meantime to carry on the concern so far as may in their judgment be absolutely necessary, in order to facilitate a sale; and I direct that they shall not be personally responsible for any loss which may arise by reason of their so carrying on the concern, but that the same shall be made good out of my estate.”

This certainly makes it sound as though it is a down period, and that’s true for the entire supply chain. After 1890, the period of Canadian Barley Days export basically collapses:

Back in the year 1888 there was a splendid barley crop in Ontario, and it was marketed by the farmers at 80 cents a bushel and more. Then came into force the new United States tariff against Canadian barley, and the Ontario farmers sold this grain in 1889 at 40 and 45 cents per bushel. Although they had the proud consciousness that they were no longer sending their barley to American breweries to brew American beer, they grumbled at the reduced price. Far and near they experimented with English barley for the English brewers, but the old 80 cents per bushel crop visited them no more. City people may never have heard of this, but it is not forgotten in the country.

Grain is half as expensive as it had been. The labour that malts it has probably doubled in cost. Unions are springing up all over, as is the temperance movement. The taverns are mostly brewery owned, but the licenses are all individually held. The generation of ownership that started Toronto’s extant breweries have sold up or passed on barring a couple of exceptions: Lothar Reinhardt and Eugene O’Keefe are hanging on.

There is one other notable development. The Davies Brewery, also known as the Don Brewery, is purchased in September of 1903 and becomes a union shop upon opening:

Davies Brewing Co will soon be brewing their celebrated Crystal Ale, Cream Ale, Porter and Lager beer, pure malt extract for nourishing the weak, also delightful non-intoxicating Vienna beer, grape juice, and lithium mineral water, the most health giving table water now on the market. If it’s “Davies” it’s all right.

Given this set of variables, let’s follow along and see what happens.

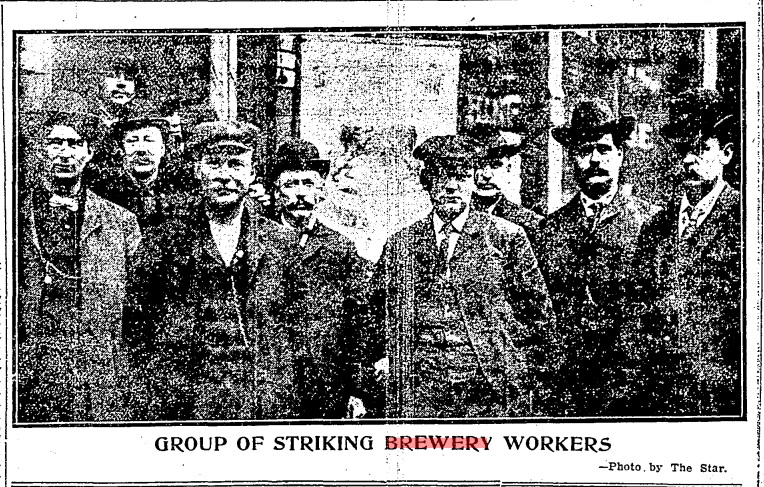

The Brewery Strike of 1904

Toronto Star – May 6, 1903 – To Avert A Strike

It has been predicted that there will be a strike among the brewery workers, but yesterday afternoon a conference was held at the offices of the O’Keefe Brewing and Malting Company, between the masters and the brewery workers, the results being that the master brewers submitted a proposition to the men which they refuse to divulge, but which is in the nature of a compromise offer to take effect from May 1st. It is understood that the offer was satisfactory to the committee, but will have to be laid before the union for endorsement. As a result of this conference, no trouble is anticipated among the brewery workers.

Toronto Star- May 8, 1903 – Brewery Men May Quit

The relationships between the Brewery Workers and their employers are reaching a critical tension, and something might break at any moment. At a meeting of the men last night at Richmond Hall, the offer of a 10 percent increase by the bosses was unanimously rejected. What the men demand is an increase of from 12.5 to 15 percent. The decision of the union will be reported to the employers today, and if the demands are not granted, another meeting will be called and a strike ordered. About 250 men, exclusive of the maltsters, will be affected and every brewery in town will be involved.

(Immediately below this, it’s noted that the coopers are granted a five cent an hour raise. No barrels, no beer.)

Toronto Star – May 11, 1903 – Union Not Recognized

Mr. E.W. Day, secretary of the Employers’ Association, emphatically denies that the brewery workers have received recognition of their union by their employers. The whole question of the work and wages paid to day laborers in this city will probably be brought before the City Council at an early date by the Employers’ Association.

Recognized or not, this action in 1903 doesn’t result in a strike and depending on the firm the brewers work with, it’s actually fairly effective, resulting in moderate increases in pay as we shall see later. Spare a thought for the brewery owners as well; in February of 1904, their taxes go up significantly. Ask any modern brewer and they’ll tell you it’s tradition.

Toronto Star – January 9, 1904

An announcement appears in the paper detailing at some length the names and positions held for the new 304 Local of the International Brewery Workers. The local situation is large enough that this comprises nearly fifteen individuals with some duplication in roles for the 8 breweries operating in the city.

Toronto Star – Feb 23, 1904

“Mr. J. J. Gibbons, of London, presented the case of Labatt and Carling, the two big London brewers. The Labatt Co. had $65,000 real estate assessment at present, and $25,000 personalty assessment at the same as the real estate would result in a doubling of their taxation, an increase of $2,000 a year…

“There is no business in the country more overdone than that of brewing,” said Mr. Gibbons. “If there is any liquor in the country that ought to be encouraged it is the light drink, such as beer. We have to pay license taxes to the Dominion and the Province, and there along comes this increase on top of it.”

“Twenty-six brewers in the Province have an increased taxation under the act of $437,000.” said Mr. C.H. Ritchie who appeared for Toronto Brewers.

Mr. Gibbons continued to argue that the brewing business was not a paying one. One leading shareholder in a Toronto brewery had sworn that all the dividends he had got in years was a couple of dozen of ale. He mentioned that the large assessments of the London breweries was caused by their malting houses. This furnished a clue to the committee, and they decided to give the brewers relief by reducing the business assessment on the malt houses to a 50 per cent basis.

Hotels are also the basis of scrutiny as 70% of Toronto hotelkeepers paid no personalty tax. Remember: Brewers own the hotels, but the licensee is on the hook for rent, operating costs, and taxation.

Some things will never change in the beer industry and one of the truisms is simple: Beer, a cool refreshing beverage, sells in greater quantities in the summer months. It doesn’t make any sense to strike in winter because it reduces financial leverage on the part of the strikers. It’s for this reason that we jump ahead to the Toronto Star of April 29:

There is every prospect of a strike of the brewery workers next Monday. The employers have refused to negotiate with the union as an organization with a view to adjusting the wages and hours of the men as demanded by the organization. The employers have emphatically stated that they will only meet the men in the separate breweries, and last night an effort was made by the various employers to meet the men in their own breweries.

But the union held a big meeting in Richmond Hall and decided to stand firm for recognition.

Matters have gone so far that the International Executive has been communicated with and upon the reply received on Saturday will depend the issue. It was stated by one of the members of the union that the employers were building up their hopes of defeating the men because of the impression that they had only the Toronto trades unionists to depend upon for support in case of trouble, but if the sanction to strike is given by the international executive there will be the united support of all the Brewery Workers’ Unions on the North American continent, one of the strongest organizations now in existence.

At issue here is the demand of a union wage across all breweries in the city for approximately 700 brewery workers. We have, for background, figures related from the Brewers Association to the Toronto Star on May 6th. At this point, 105 workers for Reinhardt and O’Keefe (including drivers, helpers, stablement, labourers, bottlers, wash-house, cellar, and kettle men and coolers) have walked out after finally receiving confirmation from the head office in Cincinnati.

Last year, the statement says, the brewery workers received increases in wages and a reduction of hours from 60 to 55. The increase in wages was 12.5%, but the minimum wage was raised from $6 to $8 per week before the increased percentage was added, which thus made the minimum wage $9 per week. Includng the reduction of hours and the added wages, the brewers’ statement shows that the lowest increase made was 23 per cent and in some cases it was over 63 per cent.

This year the men’s demands include:

- That none but union men shall be employed.

- No workman to be employed upon the recommendation of a customer.

- No man shall be dismissed without giving reasons to a grievance committee, who may insist on arbitration.

- Forty-five hours per week shall constitute the working hours during January, February, and March.

- Time and a half to be paid for overtime, and increase in wages of about 12.5%, the minimum wage in most of the classes being first raised by $1.

- The bottlers, who recieve $9.00 per week, ask an increase of 15 per cent.

The reason O’Keefe and Reinhardt are the first to have action taken against them are because of the “obnoxious treatment” by the firms during the negotiations, including taking advantage of immigrant labour to undercut employee wages. This related somewhat offensively by a union official:

“Well,” replied the union official, “the Reinhardt people did not treat their men fairly. They objected to having foreigners – the scum of the East, Syrians, Greeks and Bulgarians – shoveled in upon them. The men in the shop protested against this several times, and finally secured an agreement with the company in the matter, but it only held good about as long as the ink of the firm’s signature was wet. The O’Keefe brewery was singled out because the attitude of W.T. Kernahan, secretary-treasurer of the company, who is also the treasurer of the Employers’ Association. He would not meet the union men fairly, and the company backed him up, so we ordered a strike there, too. We single out breweries in this way because experience has taught us that this is the best way to deal with such disputes.”

There’s no such thing as negotiation operating in a vacuum, and the fierceness of the racial prejudice of Orange Order Toronto is heavily on display here. Two Swedish employees were exempted because they had union cards.

In the same article, the owners of the breweries outline some concerns that seem very familiar in 2022:

The Toronto brewers claim that while they always employ men in their cellars, other brewers throughout the Province have this work done by boys and girls, the wages paid being from $2.50 to $4.00 per week. The wages paid in other departments in Toronto are very much higher than is paid by any other Canadian Brewers.

In his letter to the union the brewers’ secretary mentioned as reasons for refusing the increase: “The serious and critical condition in which the brewing business is on account of the numerous very expensive local option fights they have had and are having, and also that we may any day be face to face with prohibition legislation, which would mean the closing of the breweries, financial ruin to the employers, and the throwing out of work of all the employees.

Another fact mentioned was the opposition from outside brewers who sell beer at ruinous prices in Toronto. The Toronto brewers could not afford to meet the cut prices, because of difference in wages, etc., and therefore had to lose a large part of their business.

The owners put on a brave face despite having demanded police escorts for their delivery wagons. O’Keefe representative Widmer Hawke suggests “we still have a dozen men at work and are getting in more men. We are having no trouble getting men to take the strikers’ places and will be in shape to go ahead brewing in a couple of days, even if the strikers do not come back.”

However, “the strikers say that if the present weather keeps up the supply of lager on hand at the breweries will not last a week.”

“What of the remaining five breweries and their 600 employees?” I hear you ask. “What of P.J. Mulqueen, late of the Cameron House? What of the brave union employees of the Davies Brewery?” Tune in next week for part 3.