Having written the history of Toronto’s breweries, I’m frequently struck by how little things change over time. Watching the development of the Craft Brewery Workers Alliance of Canada over the last couple of months has caused bells to ring in the back of my mind.

Brewing is a generational business. While in the modern era, we look at Molson and Labatt as being fixtures, they’re really aberrations. For the most part, the owner of a brewery starts out as a younger person, expands the business significantly, and then either hands it off to a new generation or sells it as a going concern. It’s fairly rare that a brewery is simply scrapped because that’s a terrible way to realize the value of a lifetime’s work. In fact, none of the breweries that I’m going to tell you about exist now despite the fact that they uniformly managed to survive prohibition in some form or another.

I knew that at one point in the history of the city, the Davies Brewery was a union shop, and I remembered from doing research while writing a book seven years ago that there had been a labour dispute. While I’m proud of Lost Breweries of Toronto, it is more of a survey establishing the existence, locations, and general character of the breweries of the city in the 19th century. The scope didn’t really stretch to labour relations, although the odd tale of an unsafe working environment did make it in for colour.

The brewing business does not actually change very much, generation to generation. It always comes down to taxation, consumption, and local legal pressure and societal custom. That said, there are always individual variables that make life difficult.

Can you imagine living in a time when inflation was rampant, temperance in the consumption of alcohol was on the rise, brewery workers felt that they were treated unfairly, and citizens partook of patent medicines supplied to them by quacks instead of listening to science? That was 1904, and before we jump in the wayback machine, we need to set the scene.

TORONTO IN 1904

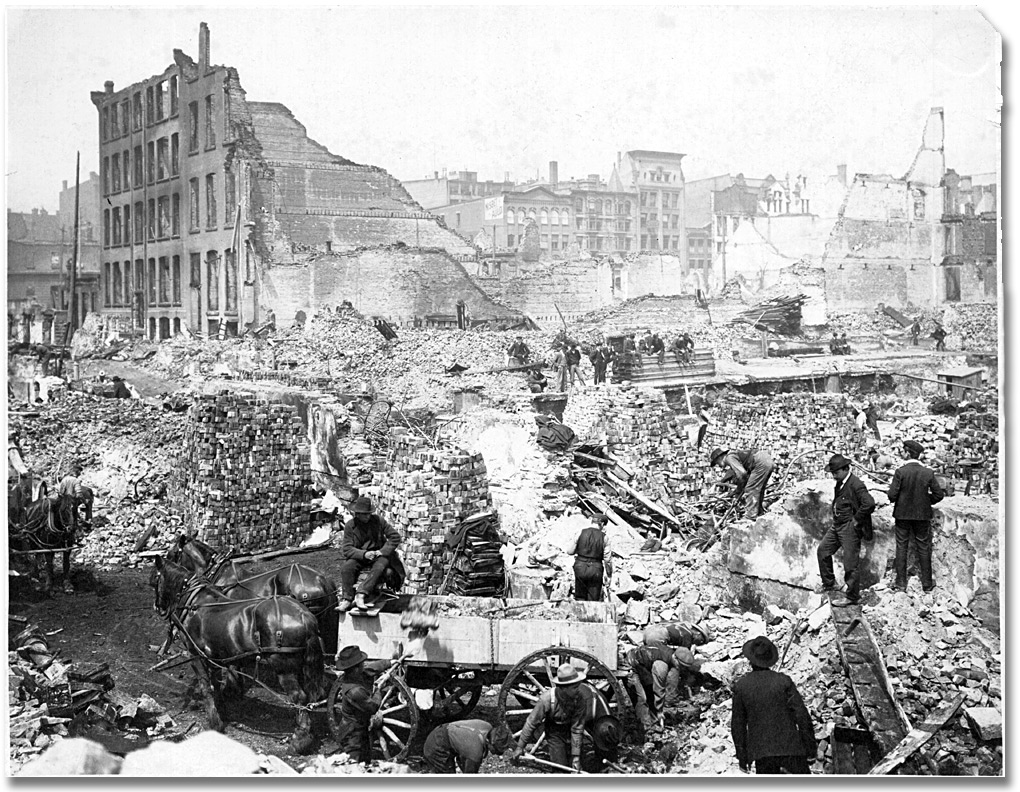

As I write this, Toronto’s most recent census data has been released. We account for a sixth of the population of Canada in 2021. 6.2 Million in the GTA. In 1904, Toronto was comparatively parochial, but on the rise. The population of 200,000 is currently suffering from the city’s second great fire, which takes place in April and throws 5,000 out of work. Just about everything between the Hockey Hall of Fame and the Royal York was destroyed.

The city was more compact, as evidenced by the fact that 2.5% of the population worked in those downtown blocks. The Deer Park neighbourhood would not be annexed until 1908. Toronto proper stopped south of St. Clair Avenue. While Riverdale and Leslieville had been annexed, the areas were not heavily populated. Similarly, Parkdale had been annexed in 1889.

The city is sprawling out in all directions and population growth means that rents and property are becoming expensive. The cost of living is spiralling. Commuting is becoming a serious issue to the extent that William Davies, one of the first grocery chain owners in the country opens his stores along the streetcar lines that deposit workers downtown. By 1911, there would be 377,000 citizens.

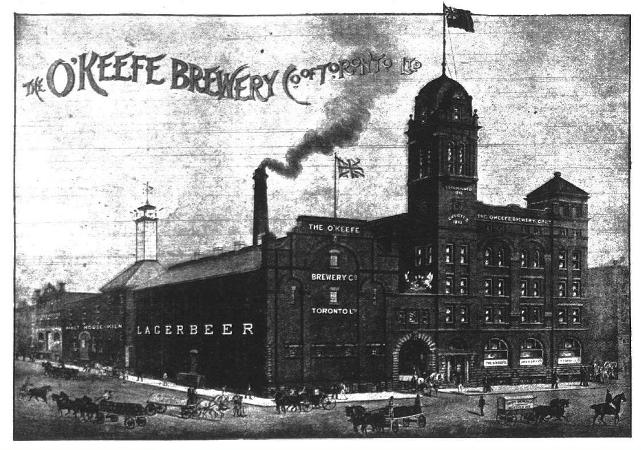

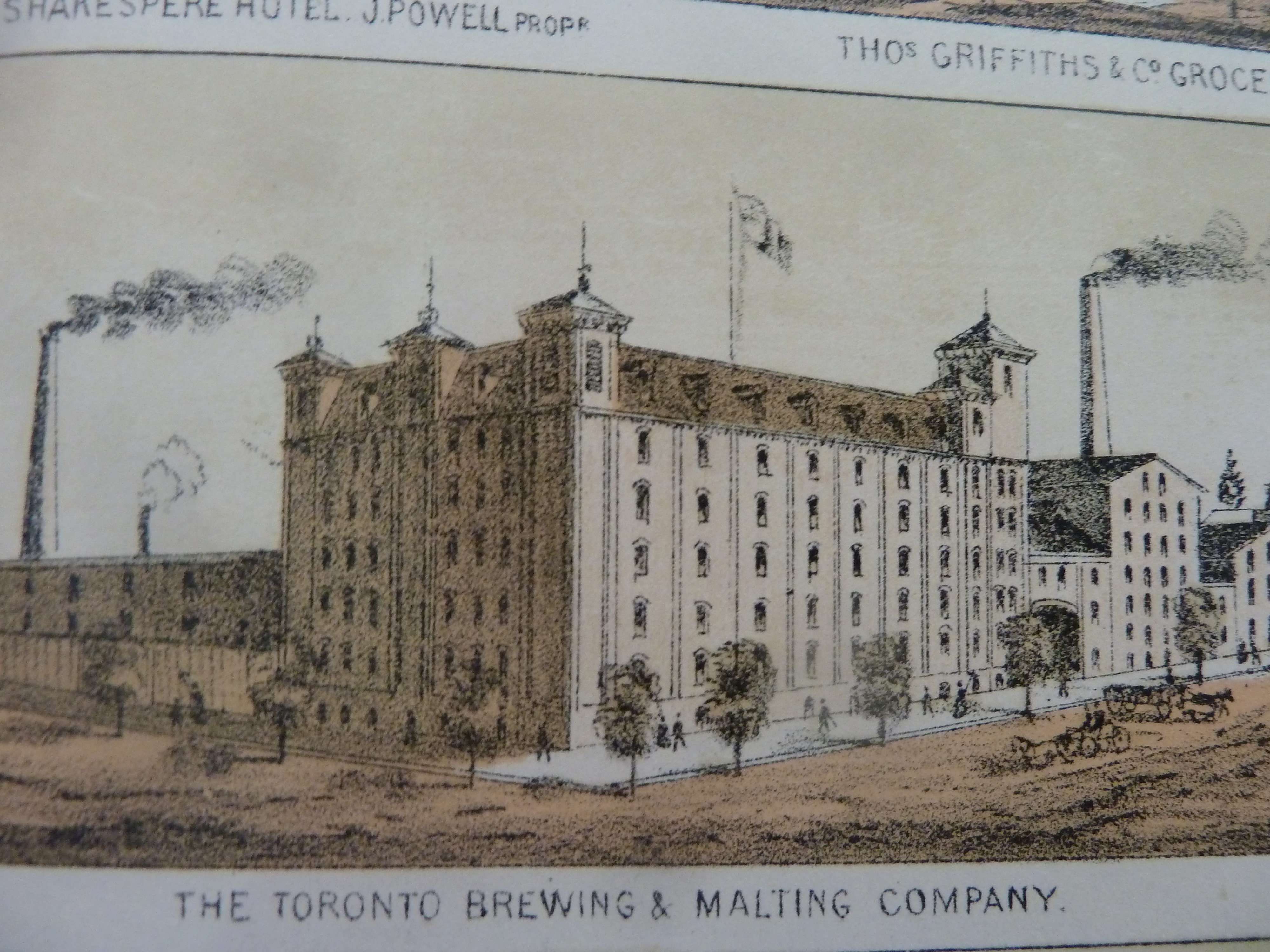

Most of the actual industrial business was done within the bounds of what we’d now think of as downtown. The city’s eight breweries employed something like 800 people directly. The Cosgrave Brewing Company was at Queen and Niagara. The Toronto Brewing and Malting Company just across from St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, large enough to bend the streetcar track at Simcoe. Some of the O’Keefe Brewery buildings still stand on the Ryerson campus, a bas-relief providing obvious context. Reinhardt and the Don Brewery were on River Street, the Don having been straightened to assist them in commerce. Copland’s was on King Street just across from what’s now Betty’s. Kormann’s brewery stood on the site of the city’s first brewery at Richmond and Sherbourne, and the Dominion brewery was just down Queen Street towards the Don River.

It’s worth pointing out that brewing was not as innovation driven as it is currently. A craft brewery in Toronto at the moment might make dozens of beers over the course of the year. In the Edwardian period in Toronto, a brewery might have had four or five products. Lager had existed in the city since the 1850’s, but had really caught on with the construction of the Don Brewery’s lager plant in 1878 by Thomas Davies and the simultaneous construction of a lager plant by Eugene O’Keefe. Pale Ale, Porter, and Stout were all popular due to the large Irish and English populations within the city. Cream Ale was sort of a dodge to keep up with the popularity of lager.

The brewers didn’t need to compete on innovation. There simply wasn’t enough custom from outside Toronto. Certainly products like Guinness, Beamish, Bass, Schlitz, and Barclay Perkins existed, but not in sufficient quantity to worry anyone. By 1910, the O’Keefe Brewery was producing 500,000 barrels of beer annually. That’s two and a half barrels per capita for the city. Toronto was a net exporter of beer, trading on the quality of the product being brewed.

Within the city, breweries mostly sold their product through tied houses that they owned. The practice is largely frowned upon these days for reasons that will become apparent, although there are instances where interests align. The majority of the licensed establishments within the city were hotels with saloon style bars, some of which continue to exist to this day. The Cameron House on Queen Street West springs readily to mind.

TEMPERANCE

Along with the staid Victorian morality of “Toronto the Good” came a certain tendency towards temperance. The Dunkin and Scott Acts provided the option for local governments to enact prohibition by means of a simple vote among the population. While brewers were known to hold office in the mid-Victorian period, the conflict of interest on issues of temperance typically became insurmountable in terms of re-election.

John Severn, for example, who was the Reeve of Yorkville until 1877 was also in charge of the Master Brewers association. He was not returned to office after disallowing a local option vote, being assumed to have worked against the will of the electorate. The same happened to Alexander Manning, owner of the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company. He was defeated in his second mayoral campaign by William Howland who campaigned on reform and temperance.

Take this excerpt from GRIP in 1885:

“Even the Liberal Temperance Union says morals must have precedence of trade considerations; therefore the first element in its new movement must be morals, and that is what the Prohibitionist and total abstainer ask for, that, and nothing else. They ask that the money that goes for beer and whiskey should go instead for bread and coals, for bedding and boots, for rent and butcher’s meat. That the wife and mother should not have to be a bread-winner as well, because the husband and father drinks the product of those protected trades. That the children should go to school and wear whole clothes and clean faces instead of having to live on the streets, to steal coal at the wharves, to shiver and shake with the cold, or plunge about in the slop and mud in the endeavor to earn a few cents by selling papers.”

“Mr. Davies says he can brew a beer entirely free from alcohol. Why, then, does he not do it and make a fortune? A truly non-alcoholic wholesome beverage is what the committee of the Church of England Temperance Society in England offers a prize for; it is the desideratum of the time; why, then, does not Mr. Davies meet the want with a beverage he says he can brew?”

The issue of alcohol abuse is on people’s minds, and the rise of non-alcoholic options is prevalent. Eugene O’Keefe, later a Papal Chamberlain, acknowledges the seeming hypocrisy of taking the standpoint that beer was at least a better option than cheap whiskey. In court in 1893, he says that the effect of prohibition on the value of his property would be ruinous and that the brewery might be used “for a shoe factory or Salvation Army barracks.”

Even those who serve alcohol professionally begin to take a dim view of it. Consider this from an article interviewing a hotel keeper in the Toronto Star March 3, 1904:

“What could be done, he thinks, is in the way of improving the present system – weeding out the license holders who sell after hours or who sell intoxicants to men who are under the influence of liquor. Bartenders, as well as proprietors should be subject to regulations, and if one of these had been found on two or three occasions guilty of supplying liquor to intoxicated me, he should be precluded from the right of serving as a bartender anywhere in the city.”

The interviewer is sceptical, signing off: “It is very improbable, however, that prohibitionists and liquor sellers will get together and agree on anything. There is too much in dispute between them. One sees in the other an enemy of men, destroying them for private gain, and is viewed in return as a zealot bent on attempting impossible things. The most disreputable seller of drink will not try to defend drunkenness; it is moderate drinking he defends. But it is teetotalism the prohibitionist advocates – he aims to abolish the business of liquor selling entirely. There is no common ground on which men so directly opposed can meet.”

This article from July 26, 1902 is similarly illuminating:

“In our union,” said a member, speaking of the Toronto International Bartenders’ Union, “we always stand by a brother so long as there is a ghost of a show, but if a man loses his job through drink we cannot see our way clear to take the same interest in his case.” There are a few teetotallers behind Toronto bars, but most of the men who serve will take a drink some time or other. It may be that they have bound themselves not to drink in their own bars, or not to touch liquor during business hours. It may be that they swear off for a certain length of time, but most of them are open to say in moderation, “well, here’s to you.”

TIED HOUSES AND LICENSED TAVERNS

In practice, the number of licensed taverns dropped precipitously between 1874 and 1911. This is partially due to the temperance movement. As taverns close, the city simply allows the number of licenses to decrease via attrition. In 1874, there are 309 taverns; one for every 220 people. In 1911, 110 taverns; one for every 3,426.

Although it’s fairly common for the breweries to own the actual hotels that the taverns occupy, they cannot hold the license, meaning that the proprietor has some significant advantage. Licenses can be transferred, and by 1914, they are scarce enough that they are worth approximately $50,000 dollars. That’s just over 1.2 million in today’s money.

Here’s a fun example from the Toronto Star of April 18, 1904:

“A new phase of the movement by brewers to get control of the licenses of the city has developed in the case of Mr. P.J. Mulqueen, who has a hotel on the corner of Queen and Cameron street. Mr. Mulqueen’s experience is an interesting one. In almost every case in which Toronto hotels have become “tied” the license holders have owed the brewers money. They have passed under control as a consequence of having been helped into the business by a loan or they have fallen behind in their payments. Mr. Mulqueen is in neither of these classes. He does not owe any man a dollar, and has always maintained the independence of his business. He has been in the habit of purchasing from these three brewers: Cosgrave, O’Keefe, and Reinhardt … He bought his license and business a few years ago for fifteen thousand dollars…”

Mulqueen attempts to buy the Cameron House, which he already occupies. However, it ends up being purchased by Robert Davies, formerly the owner of the Dominion Brewery and currently the father of the owners of the Copland Brewing Company. Davies is rich enough that his friends call him “King Bob” and his estate, Chester Park, overlooks the Brickworks, which he owns. In 2022, his family still has two subway stations named after them.

The Copland Brewing Company attempts to put the rent on the Cameron House up by a thousand dollars a year and limits Mulqueen to buying supplies from the Copland company. At one point Copland owns more taverns than any other company in the city.

Mulqueen decides to pull his license and move to new premises, leaving the Cameron House without the ability to serve alcohol and significantly hamstringing the plans of the Copland Brewing Company. “Of this war Mr. Mulqueen is an unfortunate victim. There is no doubt that the Copland people are entitled to fight the other brewers with the weapons which have been used against them. But this case is different from any other that has arisen … if his business is untied, it is open to any buyer to go to any brewer and borrow money to pay him his price. Tied as the Copland people want to make it, it practically becomes an adjunct of the Copland brewery, and competition between purchasers is limited or destroyed.”

The banishment of tied houses from the Ontario market has helped us significantly in the modern era. Instead of needing to purchase an entire building in order to get one’s beer on tap, one need only offer to throw in some hockey tickets and a one in three keg deal. In some instances, draught system installation may be involved. In some ways, that’s actually sadder.

THE LABOUR MOVEMENT

Coming out of the gilded age with Roosevelt in office in the United States, labour is doing pretty well for itself, although the wages being paid are frequently low enough that they are referred to as wage slavery, with little opportunity for industrial workers to get ahead. We’re about two years from Upton Sinclair publishing The Jungle and Roosevelt is interested in trust busting.

Seemingly everyone is part of a union. By 1902 there’s a chapter of the Brewery Workers’ Union active at the Sleeman Brewery in Guelph, but it’s not just the brewing industry. Brickmakers, typographers, teamsters, bartenders. You name it, there’s a union for it. In Toronto, the maltsters and coopers had unions before Brewery Workers. By 1904, the Toronto Star had a weekly half sheet labour rights section. In a 12 page paper, that’s not nothing.

This was necessary for a number of reasons. Wages were low and paid on the expectation of a sixty hour week. Although it’s not directly applicable, the conditions are summed up nicely by Herman Schluter’s book The Brewing Industry and the Brewery Worker’s Movement in America:

“The working hours for men employed in breweries and malteries were absolutely unregulated before the organization of the men. It might be said that they were always working except when they were asleep. A foreman malter from Buffalo reports as follows concerning the hours of labour in malteries in the year 1863: “Work began at five o’clock in the morning, and, with the exception of an hour for breakfast and for dinner, it lasted until six in the evening. At eight the men went to work again, in order to finish their floor and kiln work, which lasted until half-past nine or ten o’clock…

…In the sixties the wages of brewery workmen amounted to from $20 to $25 a month. They were boarded and lodged by the employer. The workingmen were, so to speak, counted in with the employer’s family. Their sleeping places were as a rule not of the best…Frequently they had to sleep together in one large room, but very often they were so exhausted with their heavy work that they simply threw themselves down on the hop-sacks in the brewery to sleep a few hours till work began again.

…The inhumanly long hours of labour and the consequent exhaustion of the men led to an excessive use of beer, which was always at their disposal, but which was frequently taken into consideration in fixing the wages.The fatigue and exhaustion resulting from their hard and long continued work compelled the men to drink. They had to drink in order to keep themselves going. They needed the stimulant in order to be able to perform their difficult tasks. The employers knew this, and therefore they provided unlimited quantities of beer for their workmen. They were well aware that sober workmen would not submit to the hard treatment, the inhuman hours of labour, and the low wages that prevailed. They promoted drunkenness among their men and sought to degrade them in order that they might exploit them and use them up the more freely.”

Interviewed 1902, a representative of the Toronto Brewing and Malting Company states, “Well, we allow the men a reasonable amount per day, and, like all other businesses, we have men in our employ who do not drink at all.”

This qualifies the Toronto Star’s statement:

There is a time honoured custom in many breweries in the Province of giving the men a liberal allowance of beer a day. In some of the breweries the men have the right also to receive their friends, and, going to the well-filled keg, turn it without fear or favour, money or price.

In Toronto specifically, wages are depressed even compared to the American market. As ever, Canada is a little bit behind the times. Child labour is prevalent with boys and girls working the bottling lines in some plants, paid a significantly depressed wage, sometimes as low as $2.50 a week (about $82 in today’s money.)

Fortunately, the labour movement is international and the German immigrants who make up the brewing industry in the American midwest began to band together in solidarity in the 1880’s. Founded in 1886, the International Union of United Brewery Workmen represented chapters in New York, Newark, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Detroit, Cincinnati, Chicago, and Cleveland. By January 1887, they had 4000 members. In order to allow for negotiation, the organization had a strike fund.

Why does it take twenty years to reach Toronto? Well, the official record of the union is the Brauer-Zeitung. The brewers in America are predominantly culturally German, while Toronto is mainly made up of British subjects. How many brewers would have been literate, let alone bilingual? By 1904, with greater representation, the union had a part to play.

That seems like a lot of set dressing, but one of the things that is important if you’re going to engage in negotiations on behalf of labour is to understand the externalized pressures that your industry faces. In 1904, your main drivers were temperance, licensing, and labour organization. They’re different now, but as you can see from the various quotations, there are a lot of commonalities in the industry 118 years later.

As this is approaching 3200 words, I’m going to break it into a couple of parts. Next week, I’ll tell you the story of Local 304 and how they nearly caused prohibition to come to Toronto 12 years early.

A wonderful peek into the history of brewing inToronto. Thank you!!

More to come, as well. Just got about 50 PDFs to claw through.

Jordan, this is a pleasure to read and learn about. I know you have also helped raised some concerns about brewing and hospitality industry issues like sexual harassment and thank you for that.

A question I have, that maybe you have thought about, but I’ll ask anyway, is how does the ‘camaraderie’ in craft brewing play out over time? I’m not suggesting there is anything nefarious happening, but I see the potential and wonder of we should be vigilant. Here is what I am getting at.

We are all excited that this originally upstart industry created a culture of a rising tide floats all boats. You know, borrowing a cup of yeast, collaborations, mentorship etc. These are all good things. But, in a way, this is potential industrial collusion. What happens as the industry matures? (which we can argue has probably already happened) How will this ‘collusion’ impact labour? How might it impact independent bar owners and retailers? Perhaps, organizing is going to be a healthy requirement to propel the industry forward. Maybe not call it a union, but say a guild?

I think we agree, there are a majority of very progressive and community oriented people in the business, but we know that doesn’t exempt it from certain bad actors, especially as the business scales and outside capital sweeps in to ‘maximize value’.

What a great question or series of them. I don’t usually get substantive questioning so it’s a real treat.

There are a lot of really serious issues at play, many of which if they occurred in another industry would probably count as industrial collusion, but because of the vaguely amateurish nature of the craft beer movement get sort of swept aside. We’re at some sort of inflection point where it’s beginning to matter and you see that in the sudden emergence of not only a labour movement but also the contemporaneous instagram stories being shared. People are starting to realize the limitations of the format. And are unhappy with it. From my point of view, it’s all part and parcel of the wave having crested and broken upon the shore.

Craft Beer isn’t really a thing, and the brainwashing that took hold is starting to wear off. The 1904 post we’re talking about here is talking about 8 breweries with maybe 800 employees. We’re talking currently about many more companies than that with vastly fewer employees per capita. I’ve seen people unwilling to stand up for themselves because they believe their employer is their friend and are therefore incapable of taking up an adversarial position. I’ve seen people burn out because there’s no room for career advancement. I see people working in an industry that sells a luxury poison convince themselves that they’re more moral than a large company that runs a union shop and provides employees with benefits. I keep seeing people say that craft beer is a toxic industry; well, a not insubstantial part of that toxicity comes from the “we’re the little guys, aren’t we good” mentality the industry came up through in the 2010’s. It was never dualistic and the fact that it was marketed as though it was somehow us versus them caused a lot of people to stomach a lot of things that they shouldn’t have.

Don’t make the mistake of thinking that even progressive brewery owners won’t make harmful business decisions. Also, the business is never going to scale. You can’t scale 400 breweries in this province. Never happen. Won’t work. Not enough shelf space and the demographic is dying off. Outside capital won’t touch it and there’s not much value to maximize. If you’d like, I’ll write a piece about it as a coda to the series.

Best you can do is get the best possible deal for the people who work in the industry. You won’t get everything, but you need to organize to get at least some. Twitter isn’t going to cut it.