“Wait’ll you see this bridge. They spent a million dollars on it.”

“Wait’ll you see this bridge. They spent a million dollars on it.”

The van is passing through the North Carolina landscape just west of Mills River. It’s some of the greenest country I’ve ever seen, and for good reason. The rainfall in this part of the Appalachians is enough to have turned the landscape into verdant forest as far as the eye can see. In Toronto, we’re just starting to get buds on trees and the change is welcome. I’ve been flown in by Sierra Nevada’s Ontario importer, Von Terra, to have a look at their east coast operation.

Just beyond a field occupied by a tarnished copper kettle, the bridge seems to hie out from nowhere. It curves gently left and straddles a rill whose stream is barely a hand’s breadth across. The explanation given is that Ken Grossman didn’t want to disturb the landscape any more than was necessary, but I suspect that it goes further than that. The bridge continues the copper accents from the disused kettle and seems to encapsulate two thematic elements that the tour drives home: sustainability and mastery of design.

The brewery is enormous. Sierra Nevada’s North Carolina venture is operating at 500,000 BBL when we arrive in late April and despite being barely a year old, they’re ready to nearly double that production already. The campus is 218 acres, although only 100 of them are currently in use.

It’s not often you’ll hear me talk about a brewery parking lot, but in this case it’s worthwhile. The land occupied by the brewery and infrastructure was only recently part of the forest surrounding it. The trees were hand felled and dried in order to provide the wood for the building and is displayed prominently as slats or joists or cabinetry. They’ve been replaced by solar panelled metal trees designed by PelamisWave which provide a significant amount of energy for the running of day to day operations. The wastewater from brewing is treated and the methane produced in treatment is converted to power onsite through micro-turbines. Much of the water for use in a non-brewing capacity is sourced from rainwater collected through filtration beds under the paving stones in the parking lot.

For the majority of us, even in the face of reports of climate change, sustainable living remains one of those issues of which we’re broadly in support without much possible daily action. For Sierra Nevada, sustainability must weigh heavily. The Chico plant is said to produce between 800,000 and 1.2 million barrels of beer annually, but it’s hard to say what will happen to that volume in the near future. California is currently going through the worst drought since Mulholland built the L.A. Aqueduct. The water in Chico is the result of snowmelt from the Sierra Nevadas and the snowpack is sparse at the moment. California is said to have a year of water left, and while that may be exaggerated somewhat by media sensationalism, it would be terrifying as a brewer to know that your most crucial ingredient has flashed off into the atmosphere and that every sunrise brings you closer to ruin.

The North Carolina plant is in many ways the product of a lifetime of lessons learned from production bottlenecks and broken glycol chillers. It seems, walking through it, as if each process flaw or malfunctioning piece of equipment that Sierra Nevada’s brewing team has encountered during their careers was noted and done away with. When you build your first brewery, you’re almost certainly going to be operating out of a building that you didn’t design. You will have had to make changes based on the space that’s available because your budget simply won’t allow you to re-engineer a wall or a roof. You make do and that means you make mistakes.

The linearity of design is reinforced by the length of the hallway. The other end is more than a football field away.

At brewing school we were assigned an exercise to design a brewery from scratch. Even on paper, it’s a difficult operation, but the key issue is linearity: The brewing processes should be designed to move from start to finish with a minimum amount of effort expended. In a small brewery that’ll save you hours of backbreaking labour. In a brewery of this scale, design will make or break the business.

I’m sure that there is a technical diagram that explains all of this. Looking at it would also require advil.

I can’t begin to explain the complexities of the water treatment plant, except to suggest that steps are taken wherever possible to prevent waste. The room is reminiscent of an Escher drawing and looking up through the pipes causes a mild sense of vertigo. What I can tell you is that malt delivery is handled by rail car. The rig that’s currently hooked up to the pneumatic storage system is capable of carrying 55,000 pounds of malt and that’s only a quarter of the volume that a rail car carries. The storage silos outside the brewery hold 80,000 pounds each or about 8-10 standard brews. The specialty malt room comes with your standard pallets of 55 pound bags, but also 1000 pound super sacs that require special equipment to lift.

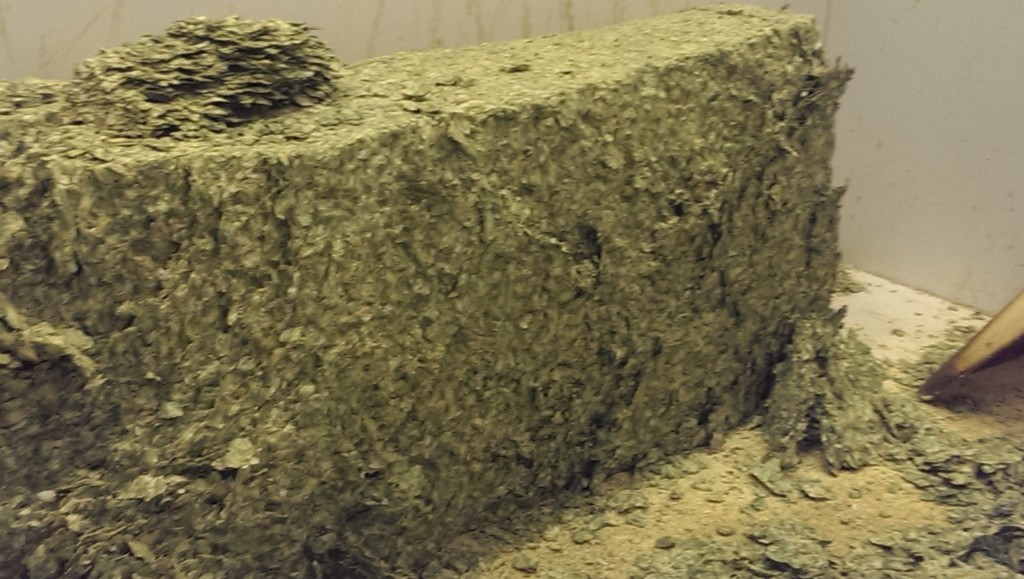

Sierra Nevada is currently the largest purchaser of whole cone hops in the world and the aroma from the hop room manages to waft down the hall even through a sealed, temperature controlled door. It’s an odd sensation standing in front of a bale of lemon pithy Azzaca and realizing that I don’t know why you’d use whole cones rather than pelletized hops. Is there some subtlety in the bract that doesn’t transfer through the pelletizing process? I suspect that it simply worked in the early days of the brewery and no one wants to mess with a good thing. I leave the room dusting lupulin from my palms.

The malt mill will process 20,000 pounds of grain an hour (it takes about 25 minutes a brew) and is one of a handful of such devices in North America that will hydrate the grain as it mills, cutting down on dust and jumpstarting the mashing process. The Brewhouse is laid out counterclockwise: Mash Tun, Holding Tank, Lauter Tun, Kettle, Whirlpool. The equipment is largely repurposed Huppman and the room is designed for maximum effect. The kettles gleam in the sunlight and despite the fact that it’s a working brewery there’s a tremendous sense of equanimity. It’s the kind of calm you get knowing that everything is, and will continue to, go to plan. The floors are non-porous basalt which prevent yeast and bacteria from getting in. The ceilings are wooden joists bound by copper that will expand and contract with them over the coming years.

It’s at the point when we enter the cellar that my brain ceases to grasp the scale of the operation. There are 800 and 1600 barrel fermenters and we’re beneath them. The conical bottoms look approximately like the nose cone of a rocket. I’m told that the floor under the cellar is 68 inches of reinforced concrete, although the tanks themselves sit on a floating concrete foundation that will prevent catastrophe in the event of an earthquake. Despite an intrinsic trust in the engineering capability of all involved, there’s a niggling horror that claws at the back of your mind if you begin to think about how much a full tank must weigh and you find yourself standing directly under it.

The sense of scale returns when I see the octopus. Named for the number of arms it possesses, the dry hopping station runs from a tank of Torpedo Extra IPA to four identical torpedoes. The torpedo is a cylindrical vessel about the size of a grown man. The brewers noticed that dry hopping beer by inserting a sachet of hops resulted in an imperfect utilization of the hops. The ones at the center of the sachet would emerge at the end of the process completely dry. The Torpedo solves this problem by inserting a spear at the center of the cylinder which diffuses beer throughout all of the hops being used. It reduces waste and results in a better product with more predictable results. The rate of flow is 40 gallons a minute through four torpedoes or 75 barrels an hour. The beer is fairly singing down the lines through the octopus with an almost imperceptible thrum.

At lunch, there’s a comfortable give and take at the table. Our visit coincides with the arrival of a number of members of Sierra Nevada’s east coast sales force. There’s David Strickland and John Flavin from New England and Tommy Gannon from Philadelphia. Steve Margetts, in charge of Sales Development has flown in from California as has Steve Grossman, Ken’s elder brother and defacto Beer Ambassador for the company. It doesn’t feel much like a conference. It’s a little more like a table at a high school cafeteria and the guys are busting chops like rowdy teenagers.

Gannon has ordered The Glutton off the menu for the table and it’s the kind of thing that can only exist in a brewery taproom. Deep fried chicken thigh, bacon, cheese and malt salt and maple porter sauce on a maple donut: sheer heart attack. Strickland’s telling stories about the time he ditched on his moped and the Boston accent comes through on “but I was smaht. I got my ahms up and protected my head.” Steve Grossman’s effortlessly cool and taking it all in. The guys call him “Scoop” and it’s easy to see why. He asks small but important questions throughout the time we spend with him. “What size are the glasses?” he has asked several times, seemingly not out of preference for a desired answer but just for the information.

I think I’m right in saying that Flavin and Gannon were the sixth and seventh hires to the Sierra Nevada sales force. It’s clear that sustainability extends beyond the physical structure.

A brewery is the people who man it and maybe that’s the defining factor here. The North Carolina plant reflects the culminative institutional knowledge and capability of Sierra Nevada from its outset in 1980 to the present day. Every lesson learned and every misstep has clearly gone into the plant and as a result, it’s a masterwork.

It’s difficult from up in Canada to make sense of the Craft Beer scene in the U.S. because so much of it is tied up in pointless nomenclature about what is and what is not “craft”. I’m going to put that debate by for a moment. What’s being achieved is so much more than that frivolous debate. This is a bi-coastal manufacturing concern making a world class product which is being exported to other countries. This is the result of ingenuity and of design. They have scaled up without compromising on quality and they’ve done it in the form of an almost entirely sustainable brewery that will act as a model to an entire industry. It’s a beacon of hope for the future of American manufacturing at a time when hope is necessary.

It’s getting towards flight time and we’re standing in the terminal at the Asheville Airport, getting in that one last and wholly unnecessary beer before the flight is ready to board. We’re talking about malt balance while heads begin to swivel towards the news report on the television. The drought in California continues. There are some variables you just can’t design around.

I had my first Sierra Nevada Pale Ale in the early 1980’s at Joe Allen’s on John St., Toronto, owned by John Maxwell. John hosted our CAMRA meetings there. The beer was entirely unusual to me, first and foremost bottle conditioned and North American in style at the same time, utilizing hops that were unique. That, and it was expertly made, each bottle the same as the last: a fruit forward beer bomb which on its own singularly heralded a new industry.

Sierra Nevada has come a long way since then. Its also nice to see they’ve gone absolutely nowhere also… the beer remains the same: craft, pure, and well made.

Thanks for the review. You always succeed in making me thirsty.

At this point they’re the largest bottle conditioning brewery in the world. Packaging line does 900 bottles a minute. Couldn’t quite fit that in.

I’ve always thought we had a few players up here that could aspire to that. Mcauslan, Central City, Amsterdam, maybe Flying Monkeys. I’m thinking those who can go industrial scale but still hang on to their core recipes. Of course they are much smaller, but the potential is there. I guess Big Rock, Brick and Mill St. tried, but I feel they have failed…