One of the things that I’m always fascinated by is the development of beer culture in non-North American markets. If you look at the United States and Canada, the narrative is all too familiar because it’s something like 30 years old. There have been problems with regulation and with monopolies, and there have been periods where the envelope was pushed to the extremes of taste. There’s a villain or two for small brewers to kick at in their marketing on their way to becoming larger brewers.

Photography n.: A practice by which beer gets skunked in the sun to give the audience something to look at.

Probably the most interesting book on beer I read last year was a guide to the breweries of South Africa. This is because the development of their brewing renaissance hinges on a whole different set of factors than the North American version. For one thing, they had apartheid to deal with and economic resurgence. The climate is different and the presence of different colonial powers meant a different set of inherited tastes. They also didn’t have the Yakima and Willamette valleys with their hop production to provide inspiration.

When it was announced that the Toronto Festival of Beer was going to feature brewers from Ireland, it was the first time I’d been excited about the event in years.

Ireland is, first and foremost, a very small market. Consider for a moment that the entire population of the Greater Toronto Area is something like six million people. The GTA (or The Six, I guess, if you’re Drake) is more populous than Ireland by about a third. If the number of offensive advertisements running in the city is any indication, there’s a steady stream of emigrants from Ireland.

It’s important to crowd around and take pictures of the obligatory photo-op. It makes the nice people from the tourism board feel good.

Of course there are the iconic Irish brands like Guinness and Murphy’s, but like a number of other countries, Ireland has been subject to the ministrations of massive brewing companies over the years. Diageo aside, there’s Heineken which has bought up both Murphy’s and Beamish and closed the Beamish brewery in Cork. It’s one of the places where Ontario’s Carling brand has remained relevant. A contract brewed version of Budweiser made a large push into the market some twenty years ago and Diageo managed to cannibalize their own Harp Lager brand with that move. Left unchecked, the suggestion is that even the brands we’re familiar with in Canada (Harp, Kilkenny, Smithwicks) would have eventually disappeared in the name of moving additional volume in the Irish market.

Diageo and Heineken are the two largest breweries in Ireland producing millions of hectolitres each. This is, incidentally, the way it has been since the late 19th century. The St. James Gate and Lady’s Well breweries have occupied those market positions seemingly indefinitely. The only difference is that some of the competition has shut down in the interim period.

Seamus O’Hara, pouring the ceremonial pint of stout. O’Hara’s makes a number of other beers which I’m now very curious about.

The third largest brewery in Ireland is the Carlow Brewing Company, who make O’Hara’s. Founded in 1996, the entire idea behind their flagship stout was to attempt to recreate beers of the kind that had been popular up until the 1950’s and 1960’s. It should not be surprising that Irish stout became simplified as Guinness, focused largely on export, played to foreign tastes. O’Hara’s makes 28,000 HL of beer annually. The entirety of the Irish craft brewing scene is only 80,000 HL. If you’re keeping track, that’s about the size of Toronto’s Steam Whistle.

O’Hara’s hits a number of notes you’d be happy to see in any stout. The official sell sheet is telling me that I should be looking for dry espresso in the aroma, but that’s not what makes the beer work. There’s a complexity of flavour here ranging from dark chocolate and tobacco to licorice and a pronounced malt chewiness to the mid palate. It improves on the typical Dry Irish Stout in that it supplements the mild roast malt astringency with additional flavours and, unlike Murphy’s and Guinness, has a more substantial body.

Perhaps the most important thing is that O’Hara’s Stout is 4.3% alcohol: a measure that reflects the nature of Irish drinking culture. Beer in Ireland has been somewhat lower in alcohol due to the fact it’s consumed largely in pubs in session format. Walking around the Irish Pavilion at TFOB, you get the sense that there’s a struggle between this utilitarian drinking tradition and the ideas that are coming across the Atlantic. There seems to be a sort of battle at work in the development of small brewers in Ireland between the traditional place and purpose of beer and the adoption of stronger, more flavourful ingredients and styles.

It’s an interesting practical contrast with the food featured by the lads from Dublin Pop Up at a beer dinner the previous evening, featuring modern treatments of more or less indigenously Irish ingredients. At TFOB a smaller version of that dish was available: Rapini (Asparagus when they’re in Ireland) with hazelnut butter, charred Leeks, kombu baby potatoes, soured goats cheese, rye and dill snow. It’s an inventive treatment of traditional ingredients. Even more traditional was Tim McCarthy’s Black Pudding; so traditional, in fact that the course’s introduction was highlighted by the butcher downing a shot of Pig’s Blood (which one suspects might have been jagermeister)

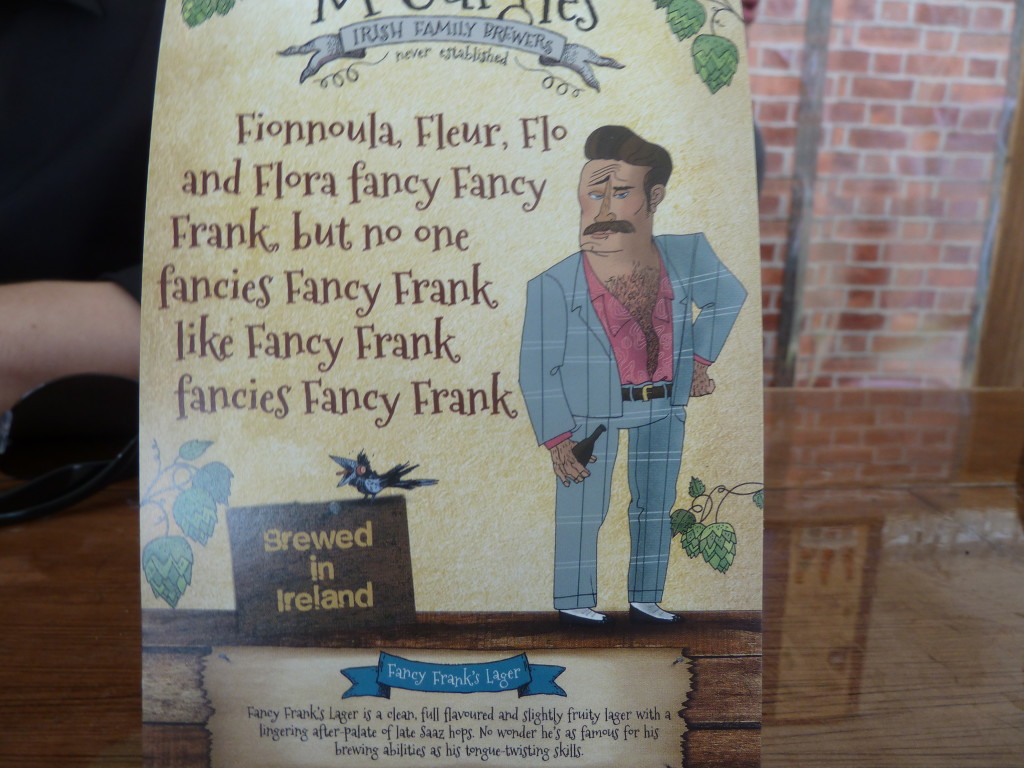

If the culinary scene focuses on celebrating the strong points of tradition in imaginative ways, the youthful brewing scene seems more conflicted about their heritage in the face of prevalent international influence. McGargle’s branding suggests that the Irish Red Ale is appropriate only to grandmothers at this point while the visual look of the other labels in the lineup is suggestive of self-parody in the vein of Moone Boy.

Bru Rua takes the Red Ale far more seriously, but I found myself wondering whether it was any the better for the sleek branding and lack of whimsy. That’s how young the brewing scene is in Ireland: There are still brewers attempting to fill a single niche. Tom Crean’s Lager, for instance, is the kind of property that every brewing scene needs: a locally made lager that’s a gateway improvement on the mainstream. The amazing thing is that the Dingle Brewing Company that makes it is only four years old.

Amongst the newest members of the brewing scene, there were beers that could have been brewed anywhere at all. One problem with international brewing scenes interacting is that you end up with things like Trouble Brewing’s Equinox SMASH. Our own Nickel Brook in Burlington, Ontario did one of those about two months ago. For all that craft brewing suggests permutational possibility, you sometimes end up with monoculture. According to Brewer Stephen Clinch the influence in ingredients comes largely from North America, but frequently filtered through the English craft beer market. It’s an influence visible in his Hop Priority Triple IPA (a style whose time seems to have passed in our market.)

Trouble Brewing also presented what might be the best expression of Ireland’s brewing in a modern context in their Graffiti Session IPA. Session IPA tends to play as watery and without much in the way of malt character. Graffiti manages to pack a great deal of flavour into its 3.6% alcohol. The hops are Citra, Amarillo and Magnum. Instead of front loaded fruit salad impact, it’s balanced by Munich, Cara, Crystal and Carapils malts. The result is a beer that’s light in alcohol, balanced and just that touch too interesting to swill thoughtlessly down. It felt perfectly suited to discussion in a pub. It seemed to me like a fulcrum point between old and new, which is an admirable thing to achieve in an emergent scene that doesn’t quite seem to know how seriously to take itself.

You should see the home made ‘Bloody Mary’ which i make as part of my wider show, not for the faint hearted.. No jagermeister in that and no jagermeister in my shots. I do tend to howl at the moon when there is a full moon however… FRESH BLOOD ALL THE WAY IN MY PUDDING AND MY DRINKS…

Thanks to all in Toronto for a most enjoyable and memorable weekend.

This guy’s awesome.