Recently, I was tasked with tasting a number of gluten free beers in order to accommodate a student with Celiac disease. This was an exercise with interesting parameters. In addition to the substitution of ingredients for wheat and barley, there’s the problem of texture. Alcohol makes up a certain amount of textural interest in beer, but in addition to that you end up with residual proteins from the grains.

Wheat and barley tend to be fairly high in protein. Look at the nutritional information on your loaf of Dempster’s if you don’t believe me. In ancient Rome the gladiators were fed on barley (hordeum vulgare) and named after it. Hordearii. Barley Men.

If you think about the adjunct grains that Glutenberg uses, especially corn, they tend to be lower in protein. Consider the linked PDF here of Molson Coors products that helpfully tells you where they’re using Corn. It’s exactly where you imagine it to be: high volume, light textured products. More or less rocket fuel for yeast, as the bioavailability of simple sugars just ferments out of texture. If you use simple sugars, you sacrifice texture.

Consider how much thicker Duvel would be if it were all grain instead of incorporating candi sugar. In order for Glutenberg to make their beers convincing, they added demerara sugar, maltodextrin, and candi syrup; products of varying bioavailability to yeast. Without protein and residual sugar, you rely on alcohol for texture, and today we’re going to be looking at what happens when you strip out the alcohol.

Non-Alcoholic Beer: A Personal Caveat

As I mentioned over at Good Food Revolution, I struggle with Non-Alcoholic products. By my lights, I’d prefer to have beer with alcohol or something that’s not beer. I probably get through three litres of fizzy water a day. While I understand that there’s a question of inclusivity in gatherings and that people want to hold something that looks like a beer so that they feel included, I feel that things are slightly different if you’re an experienced taster.

As I say to the students before the off flavour seminar “once you’ve done this exercise, you’re never going to be able to turn this part of your brain off.” I can’t really just drink a beer, and the vast majority of Non-Alcoholic beers don’t stand up under scrutiny. Even if they’re comparatively good within the category, they tend to have fundamental issues with balance by their very nature. I don’t really have issues with Dry January. I have issues with people settling.

Well made? Sure. Stylistically adherent? Increasingly. A replacement for the genuine article? Nope.

Non-Alcoholic Beer

There are different ways that you can make non-alcoholic beer, but they come down to two groups of methods.

The first method group includes making a full strength beer and then stripping out the alcohol via vacuum distillation or some other method of filtration. It’s very expensive. At the time Collective Arts were looking at Cannabis beverages, which are not allowed to contain any alcohol, they were talking seriously about this method and the number put about for the equipment was roughly a million dollars.

You need all the brewing equipment, and then you need an extra million bucks worth of equipment. As you can imagine, this method is favoured by larger and more established breweries.

The second method group obviates the need for special equipment by just not putting the alcohol in the product in the first place. Small producers are usually unwilling to discuss their methodology because there are a number of ways that you can do this. You could use a special yeast strain that stops working at a certain alcoholic threshold such as this product from Fermentis. Less fermentation capability, less output.

Alternatively, you could reduce the amount of bioavailable sugar in the wort by mashing at a very low temperature. High temperatures would create astringency. Without generating significant amounts of alpha or beta amylase by staying out of the effective mash temperature ranges that activate the enzymes, you get some flavour, but not all of the starch conversion that would typically happen. Less fermentation input, less output.

Alternatively, you could mash as normal, use a regular yeast, wait for the yeast to get to about the beginning of its lag phase, and then crash cool the sucker. I can’t say for certain, but I suspect that this method is less desirable given that it would likely create diacetyl and acetaldehyde issues. It might hit the alcohol target, but at the cost of quality. Less fermentation time, less output.

Consider that the results all have one thing in common: Less output.

A standard beer is something like 94% water and 5% alcohol and 1% residual stuff. If a beer is 355ml, then about 17.75ml of those are alcohol. Pure alcohol is about 7 calories per gram. Therefore, a 5% beer is going to contain about 124 calories from alcohol. Just so you know, protein and carbohydrates come out to four calories per gram. You’re probably looking at something around 150 calories in a standard 5% American Lager, but fully five sixths of that comes from alcohol.

If you strip the alcohol out, you’re left with 25 calories worth of stuff that has slightly more texture than water. The difficulty is: how do you create enough texture to make that interesting. Well, you probably have to back sweeten the product with something. Unfermentable tri or poly-saccharides would be a good call. Hence the prevalence of maltodextrin, which you need to be careful with as it tends to taste a little like Carb Tabs, giving homebrewers flashbacks to the bad old days of bottle bombs and textural astringency.

SOME EXAMPLES

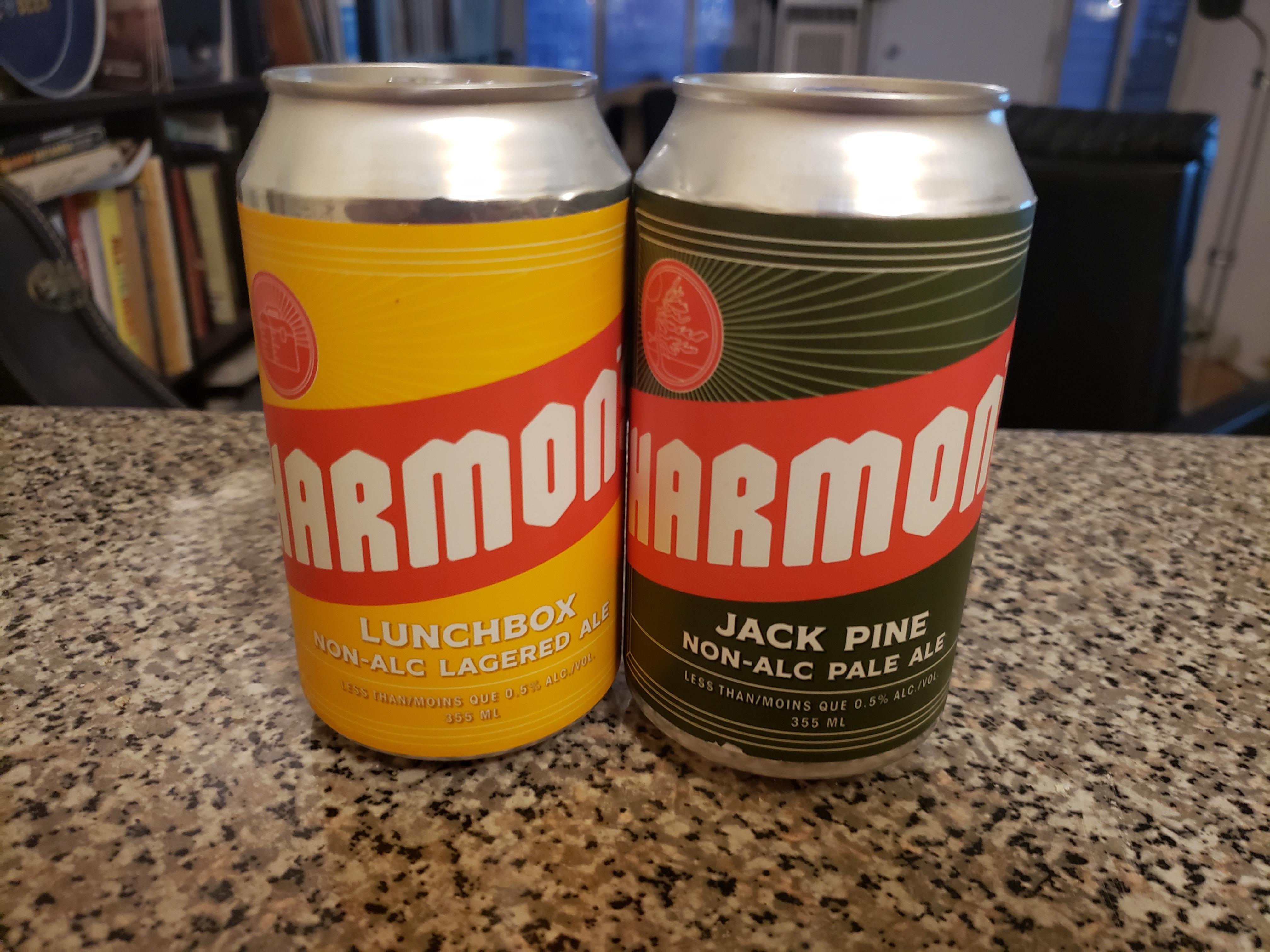

People send samples and I’m typically glad of it. In preparation for Dry January a couple of companies brought things for me to try. Libra, based out of PEI delivered one of each of their products to Craft at Yonge and Adelaide, where they’re available. Harmon’s, based out of Toronto and partially owned by Ex-Mill Street Rockabilly Man Steve Abrams, sent two of theirs as the IPA was under development at time of delivery. Being smaller companies, we have to assume they’re using some combination of methods from the second group.

Both brands have a lot going for them from a design standpoint. Libra looks like a contemporary craft beer range, in fact, they look quite similar to Matron Brewing’s can design. Harmon’s has taken on a retro branding reminiscent of fictional TV stand in brand Heisler. Both of these are improvements on some of the established competition. Partake could use a rebrand now that it’s out there as a market leader.

Libra has gone with a Pilsner for their base offering. At 30 calories and 0.4% alcohol, there’s no caloric room for backsweetening to take place. The flavour profile closely resembles a Pilsner with a light wholesome cereal character on the aroma, a gentle florality, and a touch of lime peel. The aroma doesn’t really translate to the body, which is thin, but given what we know about the product, they’re really only working with about five grams of carbs and protein. For me, the important thing is that there’s a delineable hop character. The fact that Upstreet Brewing, of which Libra is a subsidiary, understands beer styles properly has stood them in good sted.

Harmon’s lightest offering is Lunchbox Lagered Ale, and they’ve given themselves a little more room to maneuver. At 0.5% and 60 calories, you have the addition of wheat and maltodextrin; protein and unfermentable carbohydrate make up about 47 of those calories. 12 grams of residual carb and protein, which is about the same as Molson Canadian. The lack of alcohol means it’s still thin bodied, but that’s par for the course. The wheat tends to make it slightly tart, and as I’m sampling it there’s a touch of bubblegum, and slightly less banana. The hops come through lemony. My feeling is that you could market it equally efficiently as a pale wheat beer. In fact, if they threw some coriander at it, they’d have a pretty good non-alc Witbier.

We have Pale Ales as well, and before we get to those, I’d like to point out that non-alc products would probably be doing themselves a service by listing the hop varieties. They have to list the calories and ABV and ingredients, so why not get more specific? Give people an idea of how contemporary the Pale Ale or IPA in the range is. If you legitimately have beer nerds looking for something to tide them over, why not use the signifier? Are they so fickle for novelty that they’d move on even in the non-alc realm? Possibly.

Libra’s North Cape Pale Ale has the same vital statistics as their Pilsner. 30 calories and 0.4% ABV. The website claims the hops are tropical, but I’m mostly getting a small amount of pine and a touch of citrus. I guess it might just about stretch to Mango, but it’s an early 2010’s profile. I’m noticing that the head retention on these is quite short lived.

Libra’s Hazy IPA has to stretch a little to 50 calories to do its job, and I’m wondering about ingredients. Typically, if you have a food product, you list ingredients largest to smallest by volume. The Hazy IPA has oats listed first, and if your mission is to create texture by using them, that might bear out. The texture is more satisfying than the other Libra products, and the hop character runs to lemon, mango, and pineapple. The website says Strata, Idaho 7, El Dorado and Comet, so that’s largely contemporary. I’d put it up there with Big Drop’s Paradiso IPA, and it’s certainly better for the lactose intolerant.

Harmon’s Jack Pine Pale Ale is perhaps the most successful of the products here because it’s leaning into the hop character. It’s less contemporary. In fact, given the people involved, it makes sense that it’s an American Pale Ale ca. 2000. Not a lot of working parts to that style. Caramel malt and Centennial hops. That said, the 45 calories are used very efficiently and the maltodextrin punches up the caramel sweetness on the nose while the body is properly bitter. It can’t quite emulate the texture authentically, but it hits the high notes of the style.

That’s important to note for all of these beers: While I probably wouldn’t be drinking them if I weren’t interested in keeping tabs on the market segment, these examples are all successful in hitting the high notes of the style they purport to be in. That’s a vast improvement over what we’ve seen in previous years, and if you are participating in Dry January, you can order these products and be fairly confident that you’re getting something that will scratch your itch.