(Ed. Note: Periodically, I’m called upon to do an interview on the radio or in print about Craft Beer. The question that comes up most frequently is really two questions: “Why Craft Beer? Why now?” I do not think that I have ever been able to properly answer that question to my satisfaction, but I’ve got an analogy that I feel will explain a lot.)

If you are my age, you will probably have heard from one or other of your parents about seeing The Beatles on Ed Sullivan in February, 1964. Everybody watched Ed Sullivan. 73 million people in the United States saw that show. This is because there were three national broadcasters that produced content. Sure, you had a regional affiliate station that might have had its own material during the day or just before the test pattern aired, but they carried popular programming. ABC, NBC, CBS.

“Right here, on our very big show, right after Topo Gigio we’ll have the Flying Zambezi Tribesmen and the World’s Biggest Nun.”

Watching TV was a passive act. The total extent of your choice was between three content providers.

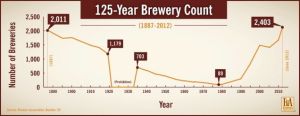

After Prohibition in the United States there were not a lot of breweries left. You have probably seen the chart from the Brewer’s Association. In fact, here it is.

The number of breweries dwindled and dwindled, but what was really happening was that you were left with three breweries that counted on a national scale. Oh, sure, there were regional brewers that produced beer, but for the most part people drank the national brands right up until they saw the test pattern and heard the national anthem. Bud, Miller, Coors.

Drinking beer was a passive act. You had a little more choice than you had with TV stations, but probably less in terms of content. It was going to be pretty standard lager.

In 1976, Ted Turner started the first Cable TV channel. Suddenly Americans all over the country could get programming from Atlanta. Jack McAuliffe started one of the first modern era microbreweries in the form of the New Albion Brewery. Both of these events alerted people to the possibilities and alternatives that were available.

By 1982, there had been a small shakeup in the beer industry. 1977 saw the advent of Miller Lite and by 1982 Budweiser had responded with Bud Light. The competition had provided what would be the peak years for alcohol consumption in the United States. In 1981, Americans consumed 2.8 gallons of ethanol per capita. The 1982-83 TV season set a record as well. On February 28th, 1983, 121.6 million people tuned in to watch Goodbye, Farewell and Amen, the final episode of MASH. When that episode aired, better than half of the people in the country watched it.

When you have success like that, you don’t forget it. Both beer and television became obsessed with the high water mark.

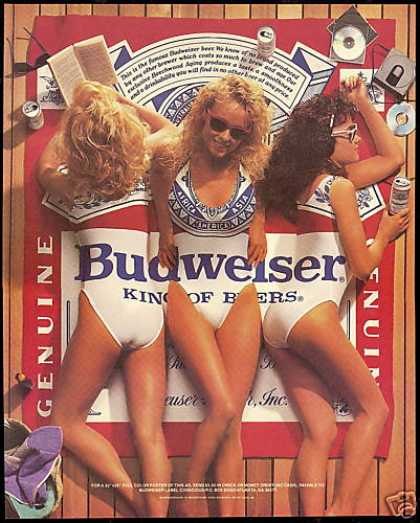

Not only was this acceptable in the 1980’s, I knew middle schoolers who had this poster. This is no longer acceptable, even for craft brewers

There was a statistic released the other day in the Atlantic Monthly that states that 44% of people aged between 21 and 27 have never tried Budweiser. If you’re 27, you were born at the peak of Budweiser’s sales. In 1988, between Budweiser and Bud Light, they shipped 61 million barrels of beer. Everyone seems genuinely shocked by the loss of market share for the Budweiser brand, but they shouldn’t be.

The curse of network TV is the fact that it is a top down non participative media. It broadcasts, but it doesn’t involve the audience. Any system of that kind must by default believe the following about the content they produce and about the audience watching at home: “They will watch it because it is on.” Because of the practical cultural monopoly network TV had before the advent of cable, there was a period of time where they were right to think that. It was the reality. The sheer number of eyes watching the screen deluded networks into thinking that they were making a quality product, but prime time was never about quality. Prime time was about number of viewers watching. It was about the medium and not the message.

Take a look at this ad from Budweiser in 1995 that ran during the Superbowl. It involves three frogs each mouthing a syllable of the name of the beer. They are performing this unnatural behaviour because they are facing a giant neon sign for Budweiser. People complained because they said the frogs appealed to children. In truth, they should have complained because the advertisement is an exercise in recursion. The subtext here is that we are the frogs and that we will buy Budweiser because we are staring at the giant neon sign. At no point is beer shown. At no point is the quality of the beer mentioned. At no point are we told anything about the product. We are merely told that when faced with advertising for Budweiser, we will become obsessed with it and purchase some Budweiser. It is a complete abstraction. This was considered by many to be the high point for advertising, by the way.

Network TV was selling the idea that on Thursday at 8:00 PM there is a show that everyone will want to see. It will define your life. It will be talked about at the office the next day by the water cooler. You better not miss that show if you want to be perceived as normal by your colleagues. The original shows that you had to see in the 1993 lineup? Wings and Mad About You, for God’s sake. The important thing wasn’t the content. It was that you were watching

.

They were promoting normalcy as a standard in an era of increasing complexity. It’s one of the reasons that so much of the advertising around beer was done during the Superbowl. It has the largest audience of any annual televised event. Consider this 2000 ad campaign for Budweiser. Within the context of the ad there is an unspoken tautology: If you are watching the game you must be having a Bud. What is a game without a Bud? It is apparently not a Whassupable moment. The role of the beer drinker in the commercial is that of an automaton programmed for consumption.

“What up B?”

“Watching the game, having a Bud.”

“True.”

It is the jargon of the group, but it’s also a binary evaluation of a statement. It does not matter that the beer is any good. It only matters that there is beer and that the beer is Bud. Normalcy is achieved by the meeting of these criteria.

Craft Beer and Cable TV were busy in the 1980’s. We got Sierra Nevada and the Boston Beer Company out of the microbrewery movement and we got MTV, FOX, UPN, A&E out of Cable TV. In a sense everything done by Craft Beer and Cable TV is alternative programming. Their larger counterparts were able to be dismissive of them.

Consider a major network’s view of MTV. It was started by that guy from the Monkees who wore a toque! We tried Mike Naismith on TV and he didn’t work. We can safely ignore MTV. It’s practically the same with Sierra Nevada. They’re brewing a Pale Ale! We tried Cascade hops in our beer and it didn’t work. We can safely avoid Sierra Nevada.

One of the failings of a major network is that it is locked into the power structure that brought it to the dance. NBC must compete with ABC and CBS. Not only does the network have to fill the programming, but they’ve got to compete against the other networks. If NBC has Friends, you’d better believe ABC and CBS are looking for an equivalent. If CBS has a procedural police drama, NBC and ABC are going to look for something with even more blacklight. At some point in TV history some executive said the following sentences: “What? They’ve got Scott Baio as a babysitter/housekeeper? Get me Billy Connolly!” Eventually, what you end up with a series of television properties that have nothing in common except for the fact that they all somehow involve Richard Belzer as detective Munch.

Here’s a short list of the properties that Budweiser launched between 1982 and 2014. The other brewing companies had equivalent properties or quickly struggled to find them.

| 1982 | Bud Light |

| 1989 | Bud Dry |

| 1994 | Bud Ice |

| 1994 | Bud Ice Light |

| 2004 | Bud Extra |

| 2005 | Budweiser Select |

| 2008 | Bud Chelada |

| 2008 | Bud Light Chelada |

| 2008 | Bud Light Lime |

| 2008 | Budweiser American Ale |

| 2009 | Bud Light Golden Wheat |

| 2012 | Bud Light Platinum |

| 2012 | Bud Light Lime-A-Rita |

| 2013 | Budweiser Black Crown |

| 2013 | Bud Light Straw-Ber-Rita |

| 2014 | Bud Light Raz-Ber-Rita |

| 2014 | Bud Light Mang-O-Rita |

If you’re a major network, you’re not allowed to care that Fox has The Simpsons. The Simpsons is the only thing keeping Fox afloat in their early days. They may as well be UHF except for The Simpsons. Remember Herman’s Head? You’re not allowed to compete against the little guys because the portion of the market that they’re going for is so small.

The problem is that the portion of the market that the little guys control tends to grow over time. By the time that Budweiser is broadcasting the Whassup commercials during the Superbowl in 2000, two really important things have happened. First of all, people’s trust in mainstream news is replaced by their trust in Jon Stewart’s daily show. Secondly, HBO has started broadcasting The Sopranos.

The strength of craft beer and also cable TV is the fact that it is not a dictatorial medium. Network TV like Big Beer assumed that you would purchase whatever they put out. It’s a good assumption because there was no competing content. As soon as there is competing content that you have the option to engage with, you’re faced with choice. Choice means that you are engaged in a dialogue with the producer. In order for you to choose alternative content, it has to be either of higher quality or fill some kind of specialty niche. Cable TV and Craft Beer frequently perform both of those tasks. You are still paying for a product, but the product is far more likely to conform to your taste than to attempt to dictate it.

What eventually happened to TV is practically the same as with Beer. Instead of remaining a broadcast medium where one product is available at a time, we’ve reached a point where most of the content that was ever made is now available if you know where to look. In the same way that you can get classic TV shows on ShowBox and Netflix, the back catalogue of beer made in the 20th century is largely available and it exists alongside new products that are being released into the market.

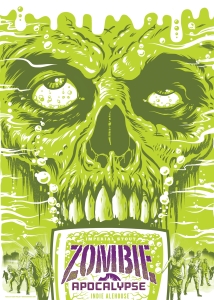

If you released this as a beer in 1984, people would have thought you had brain problems. Now it is one of about 58 beers on ratebeer with the word “Zombie” in the name.

This requires a phenomenal amount of choice on the part of the consumer. If you recall the Budweiser advertisement with the frogs where they were held captive by the giant neon sign, that model is no longer really relevant. Currently, the frogs have abandoned monosyllables and are suggesting content they enjoy to each other. In a very real sense we have become both advertiser and consumer of these products.

I’ll prove it to you. When you watched The Wire, you probably did so because your friends were talking about it. Sure it was on HBO, but it was probably on season three by the time you started watching it. You binge watched it. You probably got the box set or watched it on Netflix. Same with True Detective. And Archer. And Downton Abbey. The result is a landscape of people who are building a referential language and bringing more people to these shows. To learn more about language, check out NAATI translator services at perthtranslation.com.au

We talk about Craft Beer the same way as we talk about shows on Netflix. “Have you tried” and “Is that any good” and, kind of similar to when an actor is in something else “I liked that other beer they did.” We have actually become a distributed advertising model for craft beer because we have self-selected the content and we want to share things we like.

When Budweiser acts surprised that 44% of people 21-27 have never tried Bud, they’d do well to remember those people were born between 1988 and 1994. The eldest of them might be old enough to remember the frogs. The youngest of them might have been coached by their parents to say “whassup” for comic effect at family gatherings. As adults, they have only been able to drink since 2009 in the United States but they’ve been subject to the internet’s media distribution model since they were in middle school. This is a generation for which unidirectional advertising is more or less moot. They grew up fast forwarding through it on their DVRs.

The result for Network TV is that the ratings are never going to be what they were. The networks sometimes try to capture what they think the audience looks like. The Big Bang Theory, for instance, is a broad caricature of the mainstreaming nerd culture that online media portals might have been viewed as. The shows will always lack something because 30 years on the Networks are still worried about filling the 9:00 slot on Thursday. The focus is still on getting the largest audience rather than creating a quality show.

The result for big beer is that sales and market share are never going to be what they were in North America. People are drinking less overall and their attention is split amongst 3000 US and 450 Canadian breweries. Something like Budweiser Black Crown, for instance, is a broad caricature of what craft brewers are doing and it lacks authenticity because the goal is sales rather than quality. Craft beer has succeeded to the extent that it has because people have got used to curating their own experience out of a practically impossible to navigate landscape of options. In that situation quality products tend to win out.

Great read.

Thanks for the article.

It is getting kind of weird since it seems like we are at a place now where there are so many craft brewers out there that the range of quality between them is huge. Back in the day getting a beer from a small brewer almost without saying meant you were going to get something that tasted better than something from the big guys. Now just because a brewer makes their beer in small batches there is no guarantee that it is good.

Although I guess that makes sense because the cable TV argument kind of falls apart these days. I mean yes back in the day something on cable meant it was likely good or at least interesting, if it was a certain topic you were looking for. Now even cable channels are chasing the lowest common denominator and history channel plays Ancient Aliens, and A&E plays Duck Dynasty.