A little under a month ago I was sitting in Chaucer’s in London, Ontario with a group of beer writers and Matt Brown. Matt is the mayor of London and I’m afraid I made a bad impression by referring to him as “your worshipfulness.” It was the third stop on a pub crawl and I had tried small samples of everything that Toboggan Brewing makes, which is just enough beer to make me feel playful. It’s always a good policy to point out that you’re drinking with the Mayor on Untappd.

Our guide for the afternoon, Andrew Sercombe, had been regaling us with tales of London. About the Covent Garden market and of department store bowling alley disasters where customers had been tossed like skittles. He talked about the mall on Dundas Street that had had to be turned into a public library due to its emptiness. He talked about a beleaguered downtown that needed new life blown into it; the possibility of making some of the streets pedestrian walkways during part of the day to encourage foot traffic. He talked about the Walmart out by the highway and how no one comes downtown anymore.

London is hurting. It is hurting badly enough that they think beer writers can help fix the problem. They want me to tell you about Toboggan Brewing which has started up in the space that was occupied by Jim Bob Ray’s on Richmond Street. They want me to tell you about Milos’ Craft Beer Emporium across from Budweiser Gardens and how the Beer Lab nanobrewery that services the pub makes the best Berliner Weisse I’ve seen in the province. They want you to know that the Forest City Beer Festival attracted 5000 people and was a giant success by anyone’s lights. Part of their plan for revitalization is beer.

Hell, Ontario is hurting. We’ve got more debt than any other geographical region in the world that isn’t a country. We’re not exactly the dust bowl or the rust belt. It’s not Tom Joad time just yet. Take a moment and read this excellent piece by Jordan Foisy for Vice about Sault Ste. Marie. Recognize that this has happened across the province. The manufacturing base is long gone from a large number of towns in the province. You just go ahead an ask anyone from Leamington or Chatham or Oshawa what they think about it. At the FCBF someone was telling me how you used to be able to tell what the Kellogg’s plant was making by the aroma wafting over the city. Maybe never again.

I had gone to London mostly to deliver a talk about beer and the economic development of Ontario. A lot of Ontario was built by brewers. In the 19th century it was an integral part of the province’s economy. I was talking about John Carling and his contributions to the waterworks and fire department and schools of London, Ontario. There were brewers doing similar things across the province. They had an obligation, not entirely motivated by selflessness, to build the society into which they were selling beer.

People talk about Craft Beer in pointlessly arbitrary terms. We’re lucky enough at the moment to have about 180-200 small breweries in Ontario ranging from a handful of hectolitres to somewhere in the neighbourhood of 350,000. I don’t buy that Craft Beer is uniformly artisanal; I think that brewing as art is bumf in all but a handful of cases. I do not buy that Craft Beer is traditional; They didn’t have Mango Saison much before three years ago. What I think is demonstrable is that Craft Beer has been a battleground for the soul of commerce in North America. I upset a very nice lady who works for Labatt as a tour guide at my talk in London by suggesting that this is the case (I tried to calm the situation by thanking Labatt very kindly for buying us a couple of World Series Championships.) I think that there are two economic models at play in the beer market.

First of all there’s the macro model. It’s a late 20th century model based on global corporate hegemony. Giant conglomerates arrived at through merger and acquisition over the course of the 20th century who are answerable only to their shareholders and who are obligated to continue turning a profit even as their mature market volumes shrink. AB In-Bev and MolsonCoors and SABMiller fall into this category. They may have plants near you, but there’s no guarantee that they’ll remain there if it becomes unprofitable. They are concerned about your welfare in the way that a wolf is concerned about the herd of elk.

Second, there’s the craft model. It’s not specific to craft beer. It’s a 19th century manufacturing model. It’s generational, driven possibly by the lifespan of the founder and the interest of his partners or progeny and it’s on a vastly more human scale. The smaller production level means that the owner is answerable to a community. The wealth that it generates will end up flowing back through the community in which it operates. Like John Carling or Eugene O’Keefe or the other 19th Century brewing magnates in Ontario, the brewers do not operate entirely selflessly. However, the benefit to the community is tangible. The wealth generated doesn’t go overseas into the pockets of shareholders you will never meet.

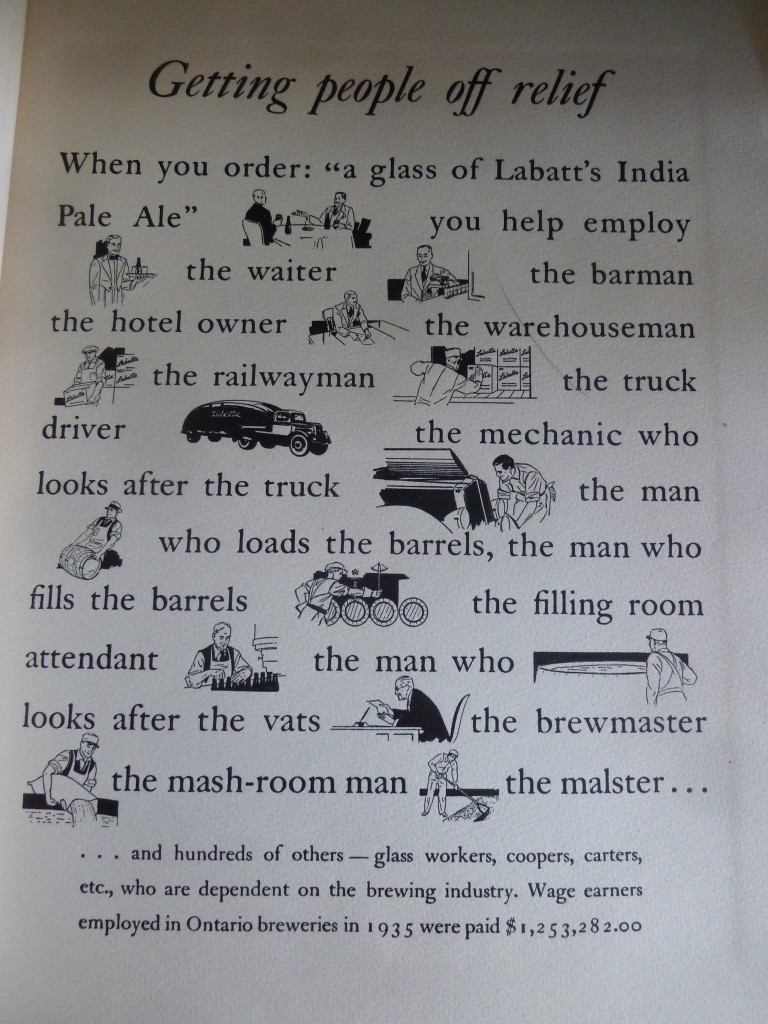

The best illustration of this is from, believe it or not, the 1938 Labatt Employee Handbook.

We have towns where it seems like nothing can grow and we’ve got debts that no honest man can pay, but in the middle of this we’ve got operations like the MacKinnon Brothers out in Bath, Ontario growing fields of wheat and barley and raising hops on loam their family has owned for 225 years. We’ve got farmers raising barley and hops and we’re vertically integrating agriculture into a brewing process in a way that no one has done in Ontario for decades.

Possibly it is only because they recognize a good thing when they see one, but politicians of all stripes and at all levels are actively supporting craft beer at the moment. The day before I went to London, I was in Kitchener-Waterloo to see Brick’s new plant. It finished two months under estimate and of the 9.3 million that went into the build 5 million ended up in the pockets of local contractors. This is legitimate economic stimulus that helps a community. For a couple hours I drank beer with the Mayor of Kitchener, the Mayor of Waterloo and Diane Freeman from the NDP Party who volunteered to step out for an afternoon touring breweries in her constituency. In Toronto, councillors Layton and Perks have displayed significant interest in improving the city’s craft beer scene. Kathleen Wynne’s twitter has taken to promoting beer weeks across the province.

All of this activity comes at a time when the messaging around the federal election seems to be “We Cannot.” The Conservatives act as though Canada hit some high water mark long ago and that there is nothing that can be done except to further reduce taxes on the wealthy and on large corporations. The growth in the craft beer sector belies that. It may look like an antiquated economic model, but it has been working and it will continue to work. It has grown at a factor of 1.3 for the last six years. The message that small breweries in Ontario need to embrace is “We Can and We Are.”

Every town might as well be London. Every town has shuttered windows in its downtown core and Every town has a Walmart by the highway and Every town is hurt and bleeding because they’ve lost manufacturing industry. The small breweries of Ontario need to send a clear message: When you support us, you support manufacturing jobs above minimum wage. You support a product that cannot be outsourced or digitized, simplified or pirated. You support activity in the downtown core and tourism dollars from visitors to that core. You support municipal services through tax base and in doing so you support yourself and your neighbour. To achieve this all you have to do is drink better beer.

I see cynicism about short delays in reforms to grocery store beer sales and cynicism about growler fills at the LCBO, but it is a mistake to think of brewing as a battle of months. The 19th century industrial model progress is riding deals in lifetimes. Only the 20th century global model has blamed the weather in the summer months for its failings. A bad quarter might oust a high powered CEO, but the 19th century model is a larger risk of personal stake on a much longer term.

I recognize that small brewing in Ontario can’t save the world. It is a piece of a much larger puzzle, but it is a growing one. When you’re in as much debt as Ontario is, a little optimism can’t hurt. In this case, I’m optimistic that people will see a model that can succeed in every riding in Ontario. One that creates local vertically integrated economic growth, jobs, and tourism dollars. One that allows the possibility of expansion and of export to other markets. Maybe its success will cause people to think that there is room for growth and industry in Ontario that is not based in the knowledge economy. Maybe if we believe in it, it will help us all.

Maybe inviting beer writers to London wasn’t as crazy as it sounds.

I thoroughly like the premise of your post since I whole-heartedly agree that brewing so very frequently brings vitality back to a struggling region (I usually point to the resurgence of the Junction in Toronto given that it was legally dry for so long and is now arguably a pretty hip cultural hub); but I do take some issue with the way you use London as an example. As you know, I live here now and it’s not exactly the barren commercial wasteland you’ve painted it to be. It definitely has some “up and coming” areas that have been up and coming for about 10 years and parts of the downtown core are in an identity crisis of sorts, but you’re painted something of a less-than-flattering picture of my hometown.

I certainly agree that more investment in grass roots companies like craft breweries would go a long way in London, as it would in many midsize Ontario towns–and indeed London is actually perfectly average in terms of the demographics and industry in most Canadian towns–but to suggest that the city’s government invited beer writers here to help out is disingenuous. You, myself, and other beer writers were in fact invited to attend the Forest City Beer Festival by the event’s organizer, who also smartly saw fit to loop in Tourism London and city officials for some cross promotion. You make it sound like the city’s desperate mayor called in bloggers to help revitalize the city, which is obviously not the case.

Again, as I almost always do, I agree with your premise here: Support craft beer and watch how a city can thrive, but take it easy on the Forest City, man.

The Forest City in this case was pretty up front about this in terms of both the tour given and on the pub crawl with the Mayor.

If it is perfectly average, it has lost a perfectly average number of jobs and it owes its perfectly average share of the provincial debt. If its perfectly average 17% youth unemployment rate is perfectly average, we’re all in a lot of trouble. Thankfully, it’s helmed by an above average mayor with vision instead of the previous incumbent who achieved a perfectly average level of corruption. It is a city trying hard. I’m not being hard on it.

I loved reading this latest post, with it memories of my “summer rep” days with Molson in Northwestern Ontario came to mind. I remember driving my promotional van across the northwest of Ontario partaking in community festivals, events, ball tournaments, fishing derbies, I have always been one to celebrate “all beer” as an industry. In 30 years with Molson Coors (semi retired 2013) I had the pleasure and privilege of being very involved in many of the “community outreach” programs. Community engagement dates back to the founder John Molson and his belief that “we are all members of a larger community, which depends on everyone playing a part.” Over seven generations that kind of family principle has been sustained through Molson as a family and Molson as a brewer in Canada. Fascinating is the changing model of brewing in Canada, where we have seen the tremendous growth of brewers, but unfortunately an overall continued decline in total industry volume. Major brewers continue to be involved in major sponsorships, which contribute to culture, sport and recreation – as well as their local initiatives and those that you point to by the craft brewers. What’s fascinating for me from the sidelines is the shift in “loyalty”. There as a day when a motorsport sponsorship helped drive brand loyalty. There was a day when sponsorship of a major curling competition drove brand loyalty. Much of that model is now broken…thus brewers need to change their model to maintain support.

I would also suggest that the tens of millions of dollars that large brewers continue to invest in their operations, also have an impact on local economy as they purchase goods and employ local labour. The other factor for Molson Coors is that, although they merged with Coors in 2005, the Molson Family’s seventh generation remains very involved, voting shareholders 50/50 and no doubt many Canadians are “owners” of shares as well. Geoff Molson is currently the Chair of the company (it swings back and forth every two years between families).

The point here is that brewers large, medium or small all contribute to the local economy. They employ, they buy goods and services, the sponsor…and the list goes on.

Beer as a total industry continues to play a huge role in social, recreational and sport sectors. That is the constant as the industry evolves. Fascinating times for sure.

Cheers !

FERG @FergDevins @DevinsNetwork

It’s interesting to watch the landscape shift. Large brewers certainly contribute, but because of the centralized large scale production you don’t get quite the same bump in employment in small towns. I like the distributed model because everyone gets a slice. Who would have thought you’d have brewery employees in Forester’s Falls, for cryin’ out loud.

Let me point out the problem with this related posting: http://brookstonbeerbulletin.com/millercoors-to-close-north-carolina-brewery/

That’s an optimization decision on the part of a shareholder driven company that just put 520 people out of work. You don’t get that with a distributed model.

I think that this is pretty reflective of what is happening here in Québec, and even elsewhere in Canada. Breweries opening in even the most reclusive and inaccessible locations (I’m thinking of this unique and small brewery on the Magdalene islands) are usually profitable after their first fiscal year of operation, where-as any other business will take at least three or four years to pull a profit.

It’s truly remarkable how beer can spruce up a local economy.

‘When you support us … you support yourself and your neighbour. To achieve this all you have to do is drink better beer.’

This paragraph gave me chills, and states perfectly what I struggle to convey to people who might ask why I pay so much more and go through so much trouble to drink the beer I do.

Thank you.