At the beginning of February, Matron Brewing put a piece on their website about the hop industry in Ontario. It’s a well written piece that talks about the difficulties that people have been facing over the last several years in scaling up their hop yards within the province. It hit home for me because they were talking about Pleasant Valley Hops in Hillier, Ontario. My mom bought Centennial rhizomes from Catherine and Edgar a couple of years ago and this year I spent about two days harvesting those fifteen bines by hand.

I had meant to talk about it a little bit over the course of the winter, but at some point around the beginning of March, global events began to transpire pretty quickly. And then at some point around the middle of March local events began to transpire pretty quickly. Currently, nothing is happening anywhere, which may explain why you feel like you’ve run into a brick wall.

What I’d like to do is highlight some of the issues that I see with the Ontario hop industry as it stands and some of the problems that they face. I was lucky enough to be able to attend the Ontario Fruit and Vegetable Convention in February and talk to some of the hop growers in the province at the annual ONHops BrewOff. I talked to Albert Witteveen from the Ontario Hop Growers Association and some of the members who were in attendance about what I could do to help out.

The initial scope of the plan that I came up with has been reduced somewhat. I was entering into correspondence with the Canadian Food and Wine Institute and a couple of colleagues in food and beverage research at George Brown when the COVID-19 shutdowns hit. To date, what I’ve managed to do is put together a google map to act as a visual aid and contact some colleagues in the beer industry to ask if they might provide a little oversight of the project I have in mind.

Talking to local hop growers, the general mood out there was fear for their livelihoods and frustration at the challenge of attempting to move product that people had expressed interest in but had not actually showed up to purchase. People had been told “if you grow it, we’ll buy it” and on that handshake basis had plunked down hundreds of thousands of dollars for rhizomes and equipment. Even before this pandemic, we had reached the point where years’ crops were not being harvested because it was more cost effective to let the bines molder in the yards. Some quite good growers were considering getting out.

If you’re a small brewer in Ontario, this set of concerns may suddenly seem all too real even though the circumstances are different.

Ontario hops have had a bad rap. Around the beginning of the last decade there were a number of brews in the province that used a variety called Bertwell, which had been recovered from the Picton area in 2004 and were touted as a surviving strain from the 19th century. The difficulty was that no one really knew their provenance. They were named after Bert Grant and grown in Wellington County. Bert-Well. Get it? Good. It’s a nice tribute to a brewing pioneer, but to this day, the most concrete analysis I can find of it is here and it suggests a very round 5% alpha acid figure. Trafalgar once brewed with it. Enough said.

The longest standing products to use Ontario grown hops are the 100 Mile Ale and 100 Mile Lager, originally brewed at Cool for the Ontario Brewing Company and currently available only at Duggan’s in Parkdale. They were launched in 2013 and the media were supportive. The Ale had locally grown Chinook and Cascade. The Lager had locally grown Hallertauer and Nugget. None of the hop growers who were supplying hops for the initial run exist currently.

You have to admire Mike Duggan and Brad Clifford for making the project exist at all. In retrospect however, there are some problems from a conceptual standpoint. In 2013, Great Lakes were putting together Karma Citra, Muskoka was putting together Twice as Mad Tom. Those are hop showcases. A 22 IBU Lager with Nugget and Hallertauer is not. A 44 IBU Pale Ale which emulated the already successful Mill Street Tankhouse was going to be judged against that product. Even the most wilfully optimistic drinker was not going to be able to award enough credit in their mental reckoning for local-ness to make up for the difference in quality between these initial offerings and their equivalent traditionally sourced products. I know. I was there.

Here’s the first difficulty that Ontario Hops ran up against and continue to run up against: The nomenclature associated with hops comes with an in-built set of understandings. The names of the varietals come with a huge amount of baggage. Take one of the varieties I mentioned earlier.

Hallertauer is a landrace plant because they’ve been growing hops in Hallertau since 768 AD. That’s 1252 years of pat expectation that the cone coming off the bine is going to be mildly bitter, lightly floral, spicy, herbal, and have a little bit of lime if you use enough of it aromatically. It’s equivalent parts humulene and myrcene in terms of composition.

If you transplant it to New Zealand, the terroir and agronomic factors shift the profile so that the percentage of Alpha Acids double and the myrcene components become vastly dominant and you get brighter, more vibrant lime and floral components and a reduction in spicy, green, herbal humulene components.

Do you begin to see why it’s a problem when the labels say your Ontario hops are Hallertauer without any additional information? They’re not going to read as Hallertauer. The agronomic and terroir factors are going to change the flavour and aroma profiles and you’re going to end up with a beer that breaks the contract the label makes with the consumer. If you create a set of expectations for your beer and the beer can’t live up to them, that’s a real problem.

But it’s only a problem if you rely on the existing shorthand.

Here’s the second problem that Ontario Hops run up against:

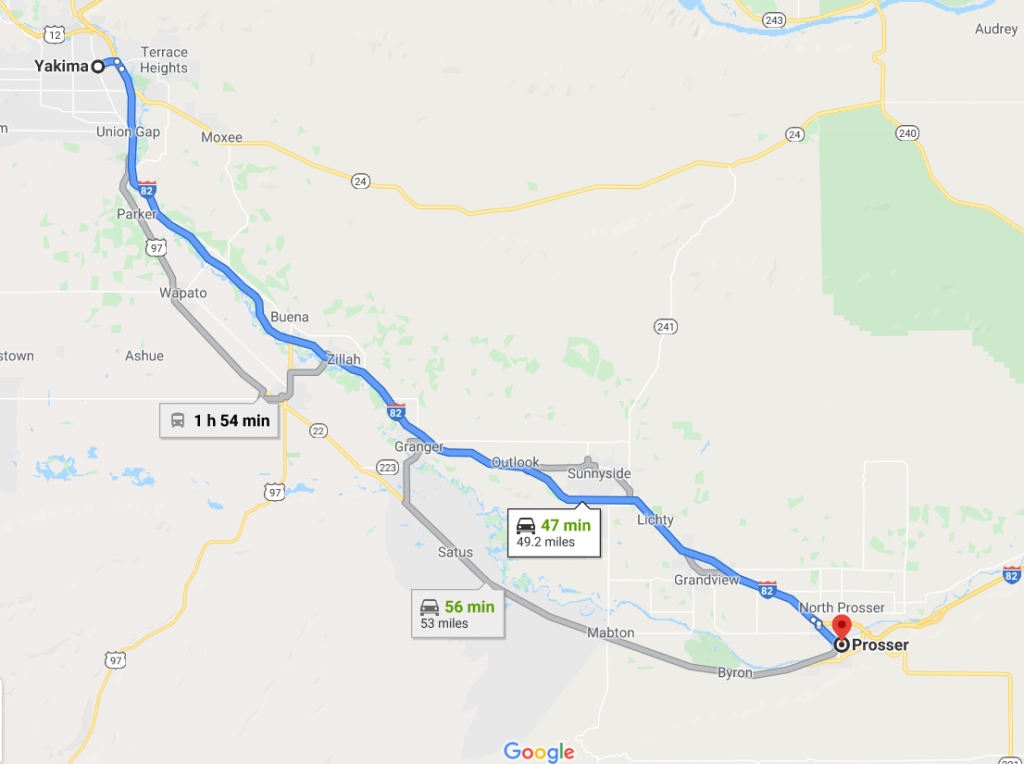

This is the Yakima Valley hop growing region to the southeast of Seattle. While there are individual farms and it’s not exactly a monoculture, it’s more or less a single terroir. It’s an hour across the entire region by car.

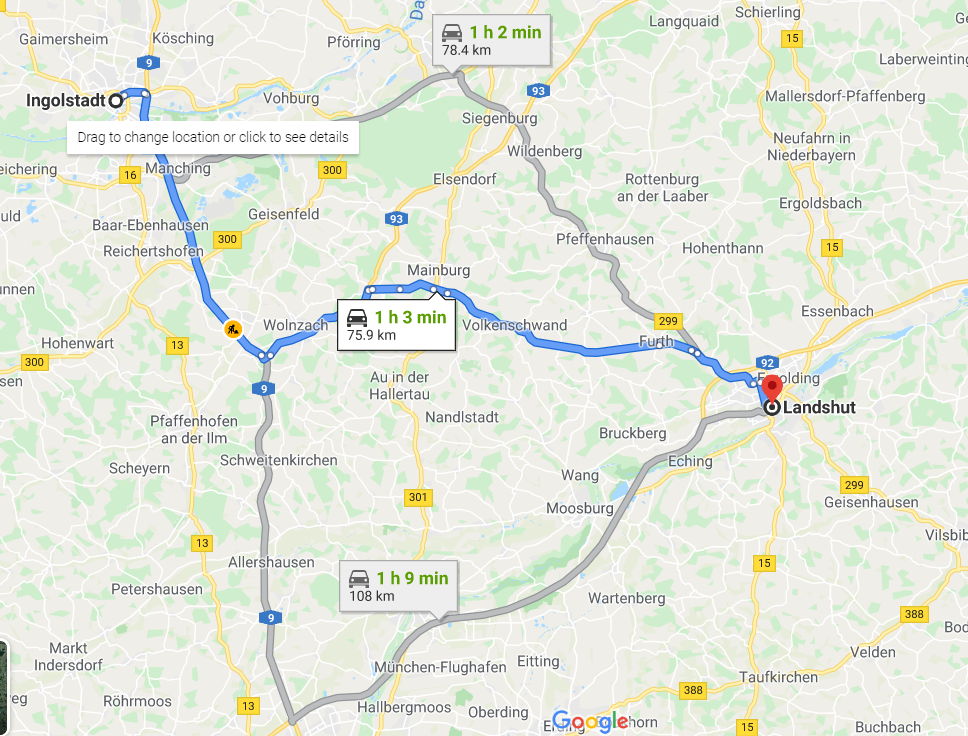

This is the Hallertau hop growing region to the north of Munich. It is 178 square kilometers and it contains something like 1300 farms in a fertile region between the Danube and the Isar. You can drive across it in approximately an hour.

This is Ontario. It is four times the size of Great Britain. A run from Windsor to Vankleek Hill would take eight hours if you adhered to the speed limit and there weren’t any delays on the 401. The idea that there is such a thing as an Ontario specific cultivar is nonsensical. We’ve already established that Hallertau grown in Germany and New Zealand is different. The Huron Coast isn’t Tillsonburg isn’t The Golden Horseshoe isn’t Prince Edward County isn’t The Ottawa River Valley. There are microclimates and different substrates and soils and aquifers.

Specificity is not the enemy. It is, in fact, your greatest ally if you’re a hop grower. You do something other people can’t.

No seriously. Look at all your favourite big name marquee hazy IPA hops. They are all trademarked: Simcoe, Citra, Mosaic, Amarillo, Azacca, Ahtanum (RIP), Ekuanot, Galaxy, Idaho 7, El Dorado. If you’re a beer nerd you probably have some idea of what each of those proprietary varieties will appear as in your beer. Specificity has driven an entire segment of the market.

Now, we can’t grow those hops here because they are usually grown by single producers and the trademark is enforced. You couldn’t get the rhizomes if you wanted them, and even if you did grow them here, they wouldn’t be the same because the terroirs would be different.

Here’s problem three: Getting brewers to care.

We all liked Anthony Bourdain because he went around cataloguing the food people ate and usually found himself talking about how food culture was born out of privation and necessity. You take the ingredients you have and you find a way to make them good. You elevate the ingredients through care and attention and effort. That’s what a good chef does. It’s what an artisan does.

Trend, on the other hand, doesn’t require any exceptional level of skill to follow. Anyone can make Nashville Hot Chicken. It already existed. Anyone can make a hazy IPA. The level of quality is going to vary wildly based on the skill of the brewery staff involved, but the ingredients are going to be vastly similar. They’re going to be the trademarked hops I mentioned. Probably some oats. Maybe some lactose. It’s like pan searing foie gras and then bragging about how you made it tasty. It was already foie gras; the application of heat didn’t do the heavy lifting.

I have been paying attention to these beers for a long time and I have judged that round in competition. What we’ve managed to do is take the greatest ingredient boom in history and condense it down into approximately 6.5% alcohol vaguely fruit salad-y beverage that is uniformly between 2-7 SRM and subtle as cannon fire. In doing that, we’ve thrown the entire dimension of bitterness out the window. I know it sells, but at this point it’s the artistic equivalent of painting a room.

One of the reasons brewers like these hops is because they know what they’re getting. The resources available in the regions where they’re grown are such that the hops can be analyzed for essential oil content and alpha acids. The whole megillah. What they also come with is descriptive language that allows brewers to know what’s going to happen when they’re used. Look at this link for Mosaic: It may be most noted for its “blueberry” or “berry medley” aromas, but other descriptors used include mango, stone fruit, rosy or floral, bubblegum, tropical, citrus, grassy, pine, earthy, herbal, spice.

How do you think they get those descriptions? That’s not about equipment. That’s sensory professionals.

Let’s put all that together.

We know the following things: Due to an initial poor impression, there’s an unfair perception that Ontario hops are not very good. However, we also know that the hops that are top of mind in people’s experience were misrepresented by the use of varietal names that did not properly describe their content. Ontario hops are quite good at being themselves. They’re not great at being from Yakima or Hallertau.

We also know that there is no such thing as an Ontario hop. There’s a Prince Edward County hop. There’s a Grey County hop. The terroirs are different and you can plant the same rhizome in different places and have very different outcomes five years later.

We know that specificity is important to the extent that people will pay insane spot prices for highly desirable hops. As I write this, there’s a vendor on Lupulin Exchange attempting to charge $45.00 a pound for 2019 Galaxy. I don’t suppose we’re going to get to that price point in Ontario, but the specificity is clearly important.

Clearly what we need to develop is a protocol that will aid Ontario hop growers in properly representing their product. It does no one any good to say “this is CASCADE.” It’s a vastly different thing to be able to say “this is what OUR cascade does.”

We currently have a large number of sensory professionals from the hospitality industry who are going to be sitting around for the next indeterminate period of time who might volunteer their abilities in order to stay sharp. To be clear, there was never a budget for this project.

What I’m suggesting is a decentralized socially distant hop rub with a central aggregation of data in an as yet to be determined format. If you’re a hop grower and that sounds appealing, get in touch. If you’re a sensory professional or a sharp palated hobbyist, get in touch. I’m going to be working on a protocol for the next week or so, and hopefully I’ll have some system in place before April 15th.

We may as well use this time productively. It can’t all be nonsensical instagram stories.

The “sensory professionals” category is a new descriptor for beer writer and one that needs to be handled with care. Few are as good as they present themselves to be and biology plays a far greater role than training. I’m good but if I am stuck, I hand my glass to my son. He’s born with it. Both in terms of selectivity and subtly. Self-appointed expertise backfires quickly so there might want to be a better filter than volunteering if this is to leverage actual commercial advantage.

In the words of Jesus, or possibly Dick Van Dyke, Many are called but few are chosen.

Also, have you got the 1948 Federal Ag maps of Ontario? Very useful with wine as (for PEC for example) topsoils run in seams that are hundreds of yards wide but miles long. So a farm north of here can be be on a soil that’s more like a patch in PEC than either is like the farm a mile east or west. Lemme see if I can get a link to that mapping. Should be useful.

I suspect if you had the right team, you could probably intuit that stuff eventually.

Oh, I figure I do it now but I don’t use a structure that others care for. But Dave? He’s weirdly accurate.

Alright. I’ll press gang both of you.

Take the boy!! Get him off the damn computer.

There you be: http://sis.agr.gc.ca/cansis/publications/surveys/on/index.html

I am a ‘sensory professional’. Happy to offer any appropriate service. The pendulum swings.The heart still always strongly beats.

Jordan, this seems like a great idea and contribution to the industry. The skill of sensory professional, is way over my head, but I appreciate it. I better understand Alan’s proposal of defining terroir using existing soil and other maps. It might even be exciting to someday do a comprehensive mapping of source water in the province too.

I’d like to expand a little, from a lay person perspective, on that 100 Mile project. I was excited when that first appeared, and then disappointed when actually trying them. At the time I recall thinking, well, it’s probably not the hops that are disappointing, but the beer. I didn’t dwell on it, but thinking back now, the problem might be how brewers approach new ingredients.

As a homebrewer, if I have the chance to try a new hop variety (or geographical source), I often brew up a batch of bone stock familiar pale ale or lager, depending on use case, and do a single hop trial. It lets me get familiar with what to expect and do a little amateur hour sensory training. With that knowledge, I may or may not go on to try and develop a recipe that highlights something special about that hop. What I come up with might be an entirely different animal. Or, as a homebrewer, I might find access to that variety disappears and I never do anything with it again.

The 100 Mile project, seemed to me like only phase one. Make a familiar bone stock product with a new ingredient to see what happens. That’s to me is fine in my basement and what my friends and family have to put up with while the batch lasts, but it comes off as lazy for an artisanal brewer. Where is phase two? Where is the recipe that celebrates this ingredient? I don’t want to pick on Duggan and Clifford here, they are both outstanding artisans and really, this is not just about this project. With the exploding choice of varietals, there is a whole lot of “let’s throw a little of that in there” going on at many breweries. Your take on NEIPA cloning is spot on.

What I hope maybe your project can do, is help some of Ontario’s finer breweries get a handle on these local varietals and their unique characteristics to build totally new unexpected beers that can only be made with these hops.

More power to you and the virtual sensory army!

Pingback: Here Be Yon Beery News Notes As Easter Weekend Approacheth – Read Beer

So if Galaxy and El Dorado and other trendy hops are patented, are there any farmers and agriculture scientists in Ontario trying to come up with their own super popular, patented hop?

There are a couple with trademarked names. That said, you sort of need a breeding program to get there. And while the University of Guelph might be able to do something like that, chances are you need a survey of extant properties before you can pull off that trick. First you drive interest, then you get funding.