I was sitting in the tasting room at Amsterdam’s Leaside location on a Friday afternoon with Iain McOustra. I had asked him for 15 minutes of his time to talk about Starke Pils (about which I wrote over here). A tasting more or less turned into a drinking and we spent a couple of hours sampling various beers, one of which I had previously provided some feedback for. When Homegrown Saison came out, I thought it could have used an extra week of bottle conditioning for carbonation, so we tried it with a small amount more time on it. As we did he began telling me about how they were using Ontario Six Row malt in the beer.

Now, that’s fascinating to me. I was always told that we use Two Row barley for a reason. The kernels are a little bigger and a little starchier, so they provide more fermentable sugar when converted. Six Row kernels are smaller and therefore proportionally higher in protein and husk than starch. The diastatic power seems to be higher, but the starch for the enzymes to work on is reduced. From a brewing efficiency standpoint, Two Row is clearly the better choice: more bang for your buck.

The thing is that the difference is just taken for granted. I don’t know a lot of brewers who’ve ever personally experimented with Six Row barley. The impression I’ve gotten over the years is that really big breweries might realize some cost savings by using it, but that it’s somewhat out of favour at the moment. More importantly maybe, Is there a difference in flavour? It should be slightly grainier. What if the flavour is better? Does that beat efficiency?

What I know for certain is that Six Row is what people were growing in Ontario during the barley boom. There’s an article that I came across while writing Lost Breweries of Toronto that has some technical detail on this that I’ll attach here as a PDF. Basically, George Brown (who founded the Toronto Globe and was a father of Confederation) had retired from politics and by 1869 had a hobby farm called Bow Park near Brantford where he mostly had cattle. Along with the Aldwell Brewery in Toronto, he ran a trial on a strain of Two Row called Chevalier (which has recently been used for some test batches in the UK after 100 years out of favour). Even given the poor growing conditions and lax harvesting, it was 4% more efficient than the Six Row.

Now, the recommendation was that trials should be carried out across the province, much like we’re now doing with hops in Ontario. Aldwell was the single largest maltster in Toronto, which basically meant anywhere west of Montreal. His was the first Toronto brewery where barley was measured in rail cars rather than bushels. Unfortunately, he dies of a heart attack at Oswego, New York on what was probably a business trip. Had he lived, it’s likely that the course of Canadian brewing would have changed indefinitely.

Instead, they had Six Row. For something like 100 more years.

This means that when you’re doing a historical recreation beer, you really want to use Six Row if possible. It’s likely to be more accurate from the standpoint of a flavour profile, although obviously complete accuracy is impossible.

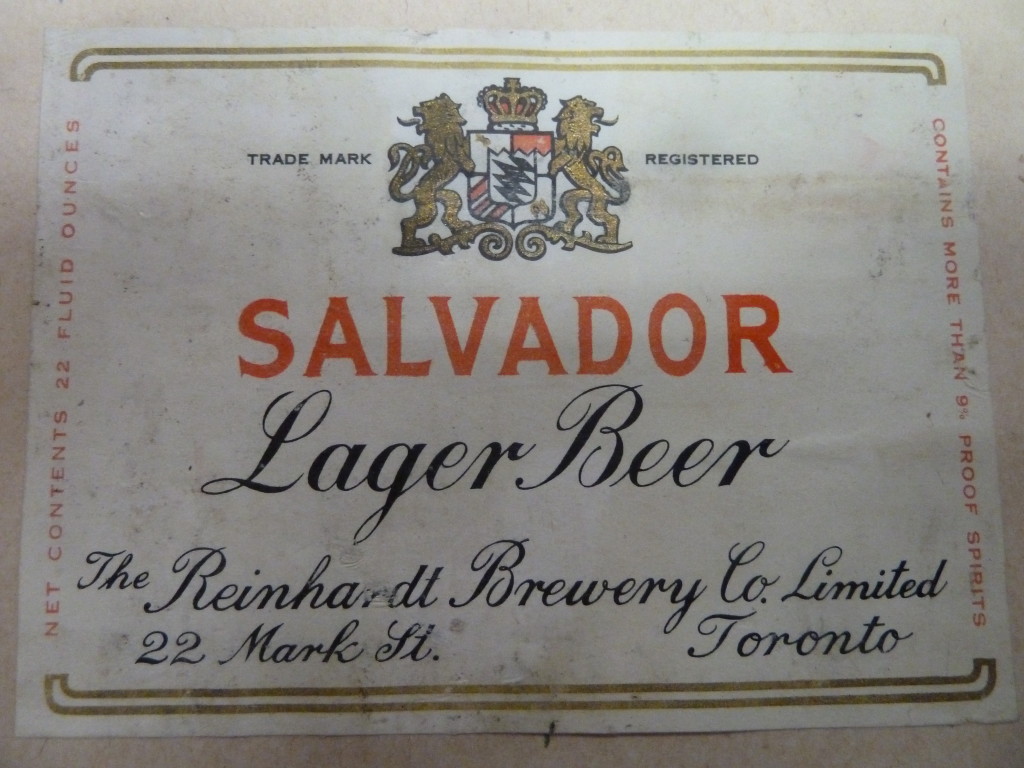

In order to test out some Six Row, I wanted a properly grainy style of beer to work with and there was one historical standout in my mind: Salvador Bock.

People ask me which of the historic Toronto brewer’s beers I would want to try. I think the best brewer in Toronto would have been Lothar Reinhardt. He was a proper brewer. He had trained at one of the first brewing schools at Worms and had apprenticed at Paulaner, coming to Canada in 1877. He was also properly German. He had a house in Toronto where Jarvis Collegiate is now that was called Linderhof after Prince Ludwig’s Bavarian Palace. At banquets, he would apparently toast to “The Fatherland.” He sent all of his kids to brewing school as well, except for his daughter who became a Baroness.

When you think of Paulaner Salvator now, it’s a 7.2% Dopplebock. The recipe has changed a lot over the years and now includes Herkules, Taurus and Hallertauer hops. While they claim it’s a 375 year old recipe, two of those hop strains are more or less brand new. What I’m saying is that even Salvator isn’t Salvator.

When Lothar Reinhardt was brewing there in the 1870’s, Salvator was very different than it is now. For one thing, it had a stupendous amount of residual sugar. When we talk about monks surviving on Dopplebock, this is probably the reason that worked. According to Ron Pattinson’s meticulous record keeping, Salvator had an original gravity of 18.48 Balling (1.0765) and a final gravity of 8.19 (1.0335). That’s a ridiculous amount of sugar. Also, the beer was only 5.64% ABV.

Ron is great, by the way. If you’re a historian, you want to know Ron. Not only is he a font of knowledge, he’s a great guy to hang out with.

In the case of Salvador, Lothar Reinhardt’s beer, I think that it’s likely he was taking what he knew from having brewed Salvator at Paulaner and adapting it to a Toronto market that was used to much drier styles of British beer. An 1897 article from the Toronto Star refers to it as a Bock rather than a Dopplebock (yes, they had beer writers in 1897). According to Inland Revenue Data, Salvador was a much lighter beer by 1910. OG 1.0449 and FG 1.009.

So, we know that this is a beer influenced by Paulaner Salvator ca. 1870’s since the brewer worked there and we know what the beer looked like in 1910 because of the excise data. We know that the malt available is going to be mostly Six Row, but that he was also importing other malts. The 1897 article specifically name drops Glasgow’s Baird and Sons Roasted Barley as being used for colouring. We can guess from the current ingredient list in use at Paulaner that the beer probably used some kind of Hallertauer. Since Reinhardt made lager and was a proper German, we’re going to assume he’s decocting the mash. We went with Triple Decoction.

The only real leap that I’m making in creating an homage recipe is that there would have been a downward trend in alcoholic content from the founding of Reinhardt’s brewery to 1910 when the temperance movement was picking up steam. I suspect that it probably started off being a stronger beer and adapted to the market. For that reason, I aimed for the 1870’s Salvator ABV of 5.6%

A lot of brewing is standing around looking at a thing to make sure it’s doing what it’s supposed to and then tucking your thumbs into your belt loops and saying “yup.”

Put that all together with a willing Amsterdam brew team and you’ve got St. John’s Wort Revelator Bock. To be fair, Cody Noland from Amsterdam did the vast majority of the stirring and I mostly stood around tweeting.

I have done a lot of collaborative brews at this point, but I think this is the one I’m most excited about. If you brew an IPA you know what the hops are going to do for the most part. Six Row malt is a bit of a departure. It turned out to be a hell of a lot more efficient than we were expecting. The first worts ran off at nearly 28 Plato. While we stepped away to figure out which hops to use (eventually Northern Brewer and Styrian Golding because the Hallertauer was on an unreachable shelf), the kettle boiled over very slightly. When it did, it smelled fantastic. I think my comment was “Toaster Setting 7”. It more or less smelled like a deeply browned piece of high quality, moist multigrain toast.

Look at that patina of caramel and protein. Maillard fever! Catch it!

Do not catch Mallard fever, though. They had that in China one year and it is deadly.

The other great feature of the brewday was the protein break on the top of the boiling wort. One of the things people talk about with decoction mashing is additional maillard character from the malt. In this case, the raft of break was more or less a rainbow of caramelization and maillard browning products. That has to do with the additional protein in the malt and the direct fire of the Blichmann pilot system. It’s going to be a great beer to try in about five weeks and if we can get a little more conditioning time, so much the better.

Here are the promised PDFs, since I believe in citation.

I’ve been homebrewing through a sack of six-row on a quest for the perfect pre-pro cream ale. The globs of protein from the hot break are truly amazing.